UPDATED 2/9/16

Mainly the candidates for the Republican presidential nomination will be fighting for a win and/or jockeying for position in Tuesday's primary. But there are couple of factors to watch as the returns come in that will affect the resulting delegate count coming out of the Granite state.

While New Hampshire does not offer a windfall of delegates, depending on how the voting shakes out the winner could end up with a surplus of delegates -- under the New Hampshire law that guides the allocation process -- that far outstrips the one delegate that separated first from third place in Iowa's caucuses. That surplus hinges on two things:

First, how many candidates finish over the 10 percent threshold necessary to claim any delegates? The current polling in the Granite state on the Republican race has Donald Trump well out in front. And while those numbers may not translate to votes, that fact does underline something perhaps more important for the candidates immediately behind the real estate mogul: the fluidity of polling in New Hampshire. Accurate or not, the polling has a number of candidates hovering around that 10 percent mark; something that has not gotten enough attention amid discussions of debate performances and impending voting.

Unlike in some other states, candidates in the New Hampshire primary receive a share of delegates in proportion to their vote. If a candidate wins 11 percent of the vote, that candidate is allocated 11 percent of the delegates. Other states proportionally allocate delegates in a manner that considers a candidate's share of the vote among just the qualifying candidates; those who meet or exceed the threshold. In that scenario, a candidate who wins 11 percent of the vote would be awarded slightly more than 11 percent of the delegates.

This is an important distinction because it leaves some number of unallocated delegates because of the threshold.

The second factor to keep an eye on as the votes are being counted tomorrow night is how much of a percentage of the total vote are the candidates not qualifying for delegates taking. A larger under the threshold percentage means a greater number of unallocated delegates. If, for instance, Donald Trump wins 31 percent of the vote and Marco Rubio places second with 15 percent, but Bush, Cruz and Kasich dip below 10 percent, that leaves 54% of the vote below the threshold. That leaves over half of the delegates unallocated.

Only, that unallocated portion is awarded to the winner of the primary. Trump would claim seven delegates for the 31 percent won to the three Rubio would win for pulling in 15 percent of the vote. However, an additional 12 delegates -- that 54 percent share -- would be allocated to Trump.

Trump, then, would leave the Granite state with 16 delegate surplus. Again, that would be 16 times greater than the cushion Cruz brought out of Iowa. This is an important point. No, not necessarily for Trump specifically, but it is these sorts rules-based differences that can be meaningful in a protracted race for a presidential nomination. If it becomes a state-to-state battle, then these delegate margins start to matter more and more.

To drive home the point about the New Hampshire rules -- and these two factors in particular -- let's go back and assume that Trump and Rubio keep their respective shares, Cruz and Kasich hold steady at around 13 percent (rather than falling below the threshold) and Jeb Bush manages to stay over the 10 percent threshold (to say, 11 percent). That is five candidates over the threshold set by New Hampshire state law with a collective 83 percent of the vote. That leaves only 17 percent unaccounted for under the threshold. Just five delegates.

After Trump takes his seven delegates and Rubio his three, Cruz and Kasich each also grab three and Bush two more. The five "unallocated" delegates are added to Trump's count for 12 delegates total and just a nine delegate surplus when compared to the 16 delegate cushion in the simulation with just two candidates above the threshold and the others below it gobbling up a significant percentage of the total vote. As the number of candidates above the threshold increases, the percentage below the threshold tends to decrease.

No, there are not a lot of delegates on the line in New Hampshire on February 9. However, the rules are in place to make New Hampshire potentially more valuable than Iowa proved to be and perhaps even some larger proportional states deeper into the calendar.

Monday, February 8, 2016

Saturday, February 6, 2016

2016 Delegate Allocation Over Time

With the first votes in the 2016 presidential nomination contests in, the races have moved out of the invisible primary and into a different phase. Concurrent with that change comes a switch in the basis for discussion. The same polls, fund-raising and endorsement data is still there, but added to that now is chatter about wins and losses and of the chase for the delegates necessary to clinch one of the parties' nominations.

FHQ is guiltier than most of digging down into that chase or the rules governing the allocation of those delegates. However, taking a step back to gain a broader view of the undulations in the process can be just as important.

Compared to the frontloaded calendars of four and eight years ago, the 2016 calendar is completely different. The February start to the 2016 process is a month later than both of the previous cycles and most of the action is packed into just two months, March and April. Eight years ago, both parties had allocated more than 80% their delegates after the contests on the first Tuesday of March. At that same point on the calendar in 2012, roughly one-third of the total number of delegates had been allocated.

In 2016?

For the current cycle, the first Tuesday in March will be the one-quarter point on the cumulative delegates allocated tally in both parties.

The national parties informally coordinated the later start and unlike 2012, actually got their way. But the allocation of delegates is also pushed into a smaller space on the 2016 calendar than was the case in 2012. The de facto national primary on February 5, 2008 when 23 Democratic and 21 Republican state voted was perhaps even more compressed than is the case in 2016.

But the development of the 2016 calendar is about the back end of the calendar as well. Four southern states -- Arkansas, Kentucky, North Carolina and Texas -- all moved from May dates in 2012 to dates in the first half of March 2016. It is the shifting of the delegates in those states along with the later start that has led to the compressed -- March and April -- calendar of events in 2016.

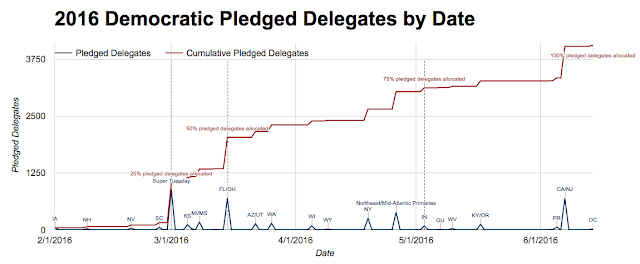

Whereas the middle 50 percent of the allocation -- between the 25 percent and 75 percent points on the calendar -- were bookended by early March and late May spots in 2012, in 2016 that middle 50 percent window in from early March to late April with a very quick ramping up of allocation between March 1 and March 15 on both parties' calendars. After March 15, the climb from the 50 percent point to the 75 percent point is much more gradual and even more subtle after that until a late flourish of allocation in early June to close the process out.

This has strategic implications. The remaining candidates -- those not winnowed by the February carve-out state contests -- have a quick burst of primaries and caucuses in the first two weeks of March. All of the active campaigns will want to develop any kind of a lead in the delegate count by then. Though the rules open up a bit on the Republican side with the closing of the proportionality window, there are limited winner-take-all states to take advantage of after that. That means that any delegate lead in either party will be difficult to close for those challenging to overtake the leader in the count at that 50 percent point.

That is because the states after the middle of March are mostly going to distribute their delegates to multiple candidates in various ways. Both catching up to a delegate leader and closing out a nomination become steeper climbs in such an environment.

Below is a look at the how cumulative growth in delegates allocated progresses in both parties in 2016.

Of note is that the Democrats are about a week behind the Republican allocation after March 1. That has much to do with there being a bevy of southern conservative states early in the process. Both parties have some form of bonus delegate calculation that that rewards party loyalty (as measured by past voting history). There are more Republican bonuses up front than on the Democratic side. Those states carry more weight in the Republican process than for the Democrats.

Note also that there are two figures for the Democrats. The first accounts for the cumulative allocation of all of the Democratic delegates. However, that includes superdelegates that will not be pledged to candidates based on the results of primaries and caucuses. When the 712 superdelegates are backed out -- see the final figure -- the picture looks largely the same among the 4051 pledged delegates. The pattern is virtually the same.

--

The Republicans

You can also find this image included with the delegate allocation information for the Republican process.

--

The Democrats

FHQ is guiltier than most of digging down into that chase or the rules governing the allocation of those delegates. However, taking a step back to gain a broader view of the undulations in the process can be just as important.

Compared to the frontloaded calendars of four and eight years ago, the 2016 calendar is completely different. The February start to the 2016 process is a month later than both of the previous cycles and most of the action is packed into just two months, March and April. Eight years ago, both parties had allocated more than 80% their delegates after the contests on the first Tuesday of March. At that same point on the calendar in 2012, roughly one-third of the total number of delegates had been allocated.

In 2016?

For the current cycle, the first Tuesday in March will be the one-quarter point on the cumulative delegates allocated tally in both parties.

The national parties informally coordinated the later start and unlike 2012, actually got their way. But the allocation of delegates is also pushed into a smaller space on the 2016 calendar than was the case in 2012. The de facto national primary on February 5, 2008 when 23 Democratic and 21 Republican state voted was perhaps even more compressed than is the case in 2016.

But the development of the 2016 calendar is about the back end of the calendar as well. Four southern states -- Arkansas, Kentucky, North Carolina and Texas -- all moved from May dates in 2012 to dates in the first half of March 2016. It is the shifting of the delegates in those states along with the later start that has led to the compressed -- March and April -- calendar of events in 2016.

Whereas the middle 50 percent of the allocation -- between the 25 percent and 75 percent points on the calendar -- were bookended by early March and late May spots in 2012, in 2016 that middle 50 percent window in from early March to late April with a very quick ramping up of allocation between March 1 and March 15 on both parties' calendars. After March 15, the climb from the 50 percent point to the 75 percent point is much more gradual and even more subtle after that until a late flourish of allocation in early June to close the process out.

This has strategic implications. The remaining candidates -- those not winnowed by the February carve-out state contests -- have a quick burst of primaries and caucuses in the first two weeks of March. All of the active campaigns will want to develop any kind of a lead in the delegate count by then. Though the rules open up a bit on the Republican side with the closing of the proportionality window, there are limited winner-take-all states to take advantage of after that. That means that any delegate lead in either party will be difficult to close for those challenging to overtake the leader in the count at that 50 percent point.

That is because the states after the middle of March are mostly going to distribute their delegates to multiple candidates in various ways. Both catching up to a delegate leader and closing out a nomination become steeper climbs in such an environment.

Below is a look at the how cumulative growth in delegates allocated progresses in both parties in 2016.

Of note is that the Democrats are about a week behind the Republican allocation after March 1. That has much to do with there being a bevy of southern conservative states early in the process. Both parties have some form of bonus delegate calculation that that rewards party loyalty (as measured by past voting history). There are more Republican bonuses up front than on the Democratic side. Those states carry more weight in the Republican process than for the Democrats.

Note also that there are two figures for the Democrats. The first accounts for the cumulative allocation of all of the Democratic delegates. However, that includes superdelegates that will not be pledged to candidates based on the results of primaries and caucuses. When the 712 superdelegates are backed out -- see the final figure -- the picture looks largely the same among the 4051 pledged delegates. The pattern is virtually the same.

--

The Republicans

Click Image to Enlarge

You can also find this image included with the delegate allocation information for the Republican process.

--

The Democrats

Click Image to Enlarge

Click Image to Enlarge

Wednesday, February 3, 2016

The Iowa Delegate Count

FHQ has fielded some questions in various forms about the delegate count coming out of Monday's Iowa caucuses. There already appear to be a few details about the minutiae of it all that are not exactly clear. Let's add some clarity to this as best we can.

The Associated Press is reporting a delegate count in the Hawkeye state that looks something like this:

Many -- well, many in my Twitter feed and inbox anyway -- have speculated and/or questioned whether FHQ just has it wrong. That there are three outstanding, unallocated delegates would, on the surface, suggest that perhaps the three unallocated delegates are intentionally unallocated. As the argument goes, those three are the three party/automatic delegates. And perhaps those delegates, as is the case in a number of other states are very simply unbound by the results of the caucuses.

It is a somewhat persuasive argument, but this is a situation where appearance and reality are at odds. Here's why:

First, FHQ spoke with Charlie Szold, the Republican Party of Iowa (RPI) Communications Director, back in August about Iowa's placement on the our primary calendar. But I took the opportunity to ask him about the newly adopted delegate allocation plan as well. Recall that Iowa's was a non-binding caucus in 2012. Adding a binding element and a proportional allocation, then, constituted a pretty large change from four years ago. Mr. Szold shared with me the new rules, I glanced them over and seeing that the Iowa rules seemed to suggest that all 30 of the delegates would be allocated and bound, followed up for assurance. After double checking with the party's expert on the delegate process, Mr. Szold confirmed that all 30 would be proportionally allocated based on the caucus results, including the party delegates.

This was a process that FHQ repeated yesterday given some pushback. The answer from RPI was the same: all 30 of the delegates, including the automatic delegates, will be allocated and bound to candidates based on the results in Monday's caucuses.

Well, here we are, two days after the caucuses, and the same 27 delegates above are the only delegates that have been allocated (unofficially by the AP). Why?

As I speculated yesterday it could be because not all precincts were in in Iowa. There is such a cluster of candidates around the 1.9 percent mark that any additions or subtractions of votes to/from the total could affect whether Fiorina, Kasich, Huckabee or Christie receive a delegate. But 100 percent of precincts are now reporting. There is now an unofficial tally. Yet, there still is not a full allocation out of Iowa.

The reason for that is that the tally is unofficial. Until the results are certified by the RPI there will not be a full delegate count out of Iowa. Let us not forget that four short years ago, Mitt Romney was declared the (narrow) winner in Iowa late on caucus night. However, a little more than two weeks later, Romney's 8 vote win became a 34 vote loss to Santorum. There is, then, a cautionary approach to the vote certification and delegate count in Iowa this time around.

Again, the issue is that four candidates are vying for three remaining delegates. Fiorina, Kasich, Huckabee and Christie all are eligible to round up to a delegate, but there are only three delegates. Christie is at the bottom of the order and would appear to be the odd man out. But it is too close to call until the vote is certified. How close? The four candidates' fractional delegate shares range from .527 to .559. That is four candidates separated by just .032 delegates. In other words, the shifting of a few votes here and there is consequential to the final delegate count.

This is a wait and see sort of thing and nothing more. The count at the top of the order -- where it matters -- is not going to change.

--

One more thing to add to this:

If one calculates the allocation of 27 delegates, the distribution would look like this:

--

Another astute question FHQ has received concerns that Huckabee delegate. And now that Rand Paul has also withdrawn, another delegate can be added to that mix. What happens with those delegates?

They stay bound to Huckabee and Paul regardless. The only out for Iowa delegates is if only one name is placed in nomination at the convention. If only one candidate is placed in nomination, as has been the case throughout the post-reform era (save one contest, the Republicans' first under the new system in 1976), then all of the delegates are bound to that candidate.

Unlike some other states, Iowa does not permit the release of delegates nor for them to become unbound in any way.

--

There are also some questions out there concerning the delegate count on the Democratic side. Much of this seems to be the result of a lack of clarity concerning how many delegates Iowa Democrats actually have. The Iowa Democratic Party delegate selection plan suggests that there are 54 delegates, but the Democratic National Committee count (still being reviewed, so not final) has Iowa with just 52 delegates, 44 pledged and 8 unpledged (superdelegates).1 It is difficult to speculate on the tentative delegate count in Iowa anyway since the delegates will not be chosen until the later stages of the process. But that process is made even more difficult when there is some doubt about how many delegates the Iowa Democratic Party has been apportioned by the DNC.

--

More post-Iowa delegate count thoughts here.

UPDATE: Certified Republican Party of Iowa caucus results and official delegate allocation.

--

1 While the link to the IDP delegate selection plan was to a draft FHQ had stowed away, I doubled checked it against the plan on the party website at the time of the original posting. It seems to have been updated as of Thursday, February 4 and now reflects the 52 delegates the DNC has apportioned to the Iowa at this time.

The Associated Press is reporting a delegate count in the Hawkeye state that looks something like this:

- Cruz 8

- Trump 7

- Rubio 7

- Carson 3

- Paul 1

- Bush 1

Many -- well, many in my Twitter feed and inbox anyway -- have speculated and/or questioned whether FHQ just has it wrong. That there are three outstanding, unallocated delegates would, on the surface, suggest that perhaps the three unallocated delegates are intentionally unallocated. As the argument goes, those three are the three party/automatic delegates. And perhaps those delegates, as is the case in a number of other states are very simply unbound by the results of the caucuses.

It is a somewhat persuasive argument, but this is a situation where appearance and reality are at odds. Here's why:

First, FHQ spoke with Charlie Szold, the Republican Party of Iowa (RPI) Communications Director, back in August about Iowa's placement on the our primary calendar. But I took the opportunity to ask him about the newly adopted delegate allocation plan as well. Recall that Iowa's was a non-binding caucus in 2012. Adding a binding element and a proportional allocation, then, constituted a pretty large change from four years ago. Mr. Szold shared with me the new rules, I glanced them over and seeing that the Iowa rules seemed to suggest that all 30 of the delegates would be allocated and bound, followed up for assurance. After double checking with the party's expert on the delegate process, Mr. Szold confirmed that all 30 would be proportionally allocated based on the caucus results, including the party delegates.

This was a process that FHQ repeated yesterday given some pushback. The answer from RPI was the same: all 30 of the delegates, including the automatic delegates, will be allocated and bound to candidates based on the results in Monday's caucuses.

Well, here we are, two days after the caucuses, and the same 27 delegates above are the only delegates that have been allocated (unofficially by the AP). Why?

As I speculated yesterday it could be because not all precincts were in in Iowa. There is such a cluster of candidates around the 1.9 percent mark that any additions or subtractions of votes to/from the total could affect whether Fiorina, Kasich, Huckabee or Christie receive a delegate. But 100 percent of precincts are now reporting. There is now an unofficial tally. Yet, there still is not a full allocation out of Iowa.

The reason for that is that the tally is unofficial. Until the results are certified by the RPI there will not be a full delegate count out of Iowa. Let us not forget that four short years ago, Mitt Romney was declared the (narrow) winner in Iowa late on caucus night. However, a little more than two weeks later, Romney's 8 vote win became a 34 vote loss to Santorum. There is, then, a cautionary approach to the vote certification and delegate count in Iowa this time around.

Again, the issue is that four candidates are vying for three remaining delegates. Fiorina, Kasich, Huckabee and Christie all are eligible to round up to a delegate, but there are only three delegates. Christie is at the bottom of the order and would appear to be the odd man out. But it is too close to call until the vote is certified. How close? The four candidates' fractional delegate shares range from .527 to .559. That is four candidates separated by just .032 delegates. In other words, the shifting of a few votes here and there is consequential to the final delegate count.

This is a wait and see sort of thing and nothing more. The count at the top of the order -- where it matters -- is not going to change.

--

One more thing to add to this:

If one calculates the allocation of 27 delegates, the distribution would look like this:

- Cruz 7

- Trump 7

- Rubio 6

- Carson 3

- Paul 1

- Bush 1

- Fiorina 1

- Kasich 1

--

Another astute question FHQ has received concerns that Huckabee delegate. And now that Rand Paul has also withdrawn, another delegate can be added to that mix. What happens with those delegates?

They stay bound to Huckabee and Paul regardless. The only out for Iowa delegates is if only one name is placed in nomination at the convention. If only one candidate is placed in nomination, as has been the case throughout the post-reform era (save one contest, the Republicans' first under the new system in 1976), then all of the delegates are bound to that candidate.

Unlike some other states, Iowa does not permit the release of delegates nor for them to become unbound in any way.

--

There are also some questions out there concerning the delegate count on the Democratic side. Much of this seems to be the result of a lack of clarity concerning how many delegates Iowa Democrats actually have. The Iowa Democratic Party delegate selection plan suggests that there are 54 delegates, but the Democratic National Committee count (still being reviewed, so not final) has Iowa with just 52 delegates, 44 pledged and 8 unpledged (superdelegates).1 It is difficult to speculate on the tentative delegate count in Iowa anyway since the delegates will not be chosen until the later stages of the process. But that process is made even more difficult when there is some doubt about how many delegates the Iowa Democratic Party has been apportioned by the DNC.

--

More post-Iowa delegate count thoughts here.

UPDATE: Certified Republican Party of Iowa caucus results and official delegate allocation.

--

1 While the link to the IDP delegate selection plan was to a draft FHQ had stowed away, I doubled checked it against the plan on the party website at the time of the original posting. It seems to have been updated as of Thursday, February 4 and now reflects the 52 delegates the DNC has apportioned to the Iowa at this time.

Monday, January 25, 2016

2016 Republican Delegate Allocation: IDAHO

Updated 3.8.16

This is part twenty-two of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

IDAHO

Election type: primary

Date: March 8

Number of delegates: 32 [23 at-large, 6 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 20% (statewide)

2012: proportional caucus

--

Changes since 2012

The date is much the same -- it amounts to the same first Tuesday after the first Monday in March date -- but the mode of delegate allocation is different in Idaho in 2016 than was the case in 2012. Republicans in the Gem state traded in their early caucus for an earlier presidential primary (moved from the traditional mid-May point where it was consolidated with the primaries for other offices).

Idaho Republicans also switched out some funky caucus allocation rules for a set of rules that is more in the mainstream of how other states are allocating delegates in 2016. Gone is the more or less instant runoff method that netted Mitt Romney a winner-take-all allocation. That has been replaced by a proportional allocation based on the statewide results of the March 8 presidential primary in Idaho. As has been witnessed in other states, though, what constitutes proportionality varies quite widely.

Thresholds

Much of that variation in the application of proportionality is attributable to a couple of factors. First, is the delegation pooled or separated for the purposes of allocation? The former typically means that a state will end up closer to a true proportional allocation of delegates than not. The latter opens the door to the bulk of the wild delegate allocation plans out there. Secondly, however, is there a threshold that the candidates must meet to qualify for delegates? With a threshold comes limitations in terms of how many candidates end up with delegates.

But that fact is tempered by the distinction raised in the first question. States that have separated allocation -- distinctions made between the allocation of at-large and congressional district delegates -- and a threshold have been the most complex. Many of the SEC primary states fit this description. Idaho fits somewhere in between states with that type of allocation and those with a proportional allocation of pooled delegates without a threshold.

It is that kind of allocation that ends up being perhaps the least complex. For example, then, Idaho Republicans will pool all of their delegates rather than invite complexity through a separate allocation of at-large delegates and the six delegates in just two congressional districts. The rationale is similar to the that of other small states. Power comes through allocating a small bloc (or blocs) of delegates rather than a much more decentralized proportional allocation.

Gem state Republicans will accomplish this through pooling their delegates but also by layering in a couple of thresholds. First, to qualify for any of the 32 delegates, a candidate must win at least 20% of the vote (before rounding) in the Idaho presidential primary. That will have the effect of limiting the number of candidates who receive delegates to likely four or fewer. If no candidate clears the 20% threshold, then the allocation would be carried out as if there was no threshold at all.

Not expressly prohibited by the rules is a backdoor to a winner-take-all allocation. While the "if no candidates clear the threshold" contingency is described, the "if only one candidate clears that qualifying threshold" is not. What that means is that there is a backdoor winner-take-all option on the table in Idaho. And since the delegates -- all 32 of them including the automatic delegates -- are pooled Idaho is the one state before March 15 where just one candidate surpassing the qualifying threshold could net that candidate all of the delegates from that state. The others to this point on the calendar that have allowed for a backdoor winner-take-all option, but the allocation was split into statewide/at-large and congressional district delegates. That makes Idaho a potentially powerful, pre-March 15 piece in the allocation puzzle. Things would have to fall right -- a crowded field with little winnowing or separation between the candidates, for example -- but a potential +32 coming out of Idaho could be more valuable to a campaign than a split of, say, the 155 delegates in Texas.

Finally, Idaho also has a true winner-take-all trigger as well. Should one candidate win a majority of the vote statewide, that candidate would also be entitled to all of the delegates from the state. This may or may not be likely in a less crowded field. The last two winners in Idaho received more than 50% of the vote.1

Delegate allocation (at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates)

The Idaho Republican delegates will be proportionally allocated to candidates based on the outcome of the March 8 primary in the Gem state. Based on the last poll conducted on the race in Idaho (the late August 2015 Dan Jones and Associates survey2), the allocation would look something like this3:

The arrival at such an outcome is a bit unconventional in Idaho. The allocation calculation calls for the candidate's share of the vote to be divided by the total statewide vote. That would mean that Trump, in the above example, would only receive a 28% share -- or 9 -- of the total number of delegates. That is not winner-take-all by any account. However, the rules also call for the unallocated delegates -- those not allocated to Trump above -- to "be apportioned proportionally among candidates who clear the 20 percent threshold." That would award the remaining 23 delegates to Trump, giving him the full allotment of delegates.

Were the backdoor winner-take-all allocation trigger not tripped multiple candidates crossed the 20% barrier -- or none did -- the Idaho Republican Party rules are not clear on how the rounding would be handled (though the allocation would be proportional without any threshold). The only reference to rounding is that a candidate must have 20% of the vote to qualify. 19.9%, for instance, would not round up to 20% and qualify any such candidate for delegates.

It is not clear, then, if the rounding is always up to the next whole number or simply to the nearest whole number. Additionally, there is no outline for a sequence to the rounding procedure or a contingency for unallocated or over-allocated delegates. That contingency coming into play is a function of how many candidates clear the threshold. Anything more than two candidates raises the likelihood that there will be an under- or over-allocated delegate.

If, however, the threshold is lowered to 15% to include Ben Carson in the allocation, then Trump would round up to 9 delegates, Carson would round up to 5 and the remaining 18 delegates would be uncommitted. That is due to the allocation equation laid out in the Idaho Republican Party rules. Only candidates over the threshold qualify for delegates, but a candidate claims delegates based on their share of the statewide vote divided by the total statewide vote for all candidates, not just the qualifying candidates. If the threshold is lowered to 7% to pull in Bush and Cruz, then Trump and Carson would be allocated the same 9 and 5 delegates respectively and Bush and Cruz would both round down to 2 delegates each. 14 delegates would be unallocated and would remain uncommitted. While the rounding in Idaho retains some operational question marks, the combination of simple rounding rules -- rounding up above .5 and down below it -- and not allocating delegates for those under the 20% threshold simplifies things to some degree.

Binding

Though the party rules use pledged rather than bound, the intent is the same with regard to how the Idaho delegates act at the national convention. Delegates are bound to the candidate who "proposed them on their list" or were pledged to by the Idaho Republican Party Nominating Committee on the first ballot of the roll call voting at the national convention. Like Hawaii, the candidates have some say in who their Idaho delegates will be. Candidates submit a list delegate candidates -- a slate essentially -- equal to 80% of the total delegation (26 delegates). Should a candidate win all of the delegates and/or fail to submit a list (or the requisite fee), then the Nominating Committee would select and pledge delegates to that candidate. In the event of a winner-take-all scenario, that would mean the remaining 20% of delegate slots not covered by the 80% slate. In the case of a candidate not filing a slate, that would mean how ever many delegates allocated to that candidate. In a straight proportional allocation of the delegates, the 80% slate is likely to contain enough delegates to cover the candidate. Again, that is 26 of the 32 delegates.

It is a little quirky, but it does highlight that the candidates would mostly retain some power over who their delegates are. That has implications for the national convention should it go beyond just one vote. Most of those delegates would be more loyal to the candidate than delegates selected and bound to a particular candidate but who prefer another.

Additionally, a candidate's withdrawal from the race or suspension of their campaign makes their delegates uncommitted. This is clear if the withdrawal/suspension occurs after the selection but before the convention. In that case, the Idaho Republican Party rules clearly release the delegates. However, if the withdrawal occurs before the selection process described above, then the Nominating Committee may fill those slots with as many uncommitted delegates as the withdrawing candidate was entitled to.

--

State allocation rules are archived here.

--

1 Granted, McCain had already wrapped up the nomination by the time Idaho voted in May 2008 and Romney benefitted from the aforementioned, quirky caucus allocation rules in 2012.

2 Though the 17% of respondents who fell into the "Don't Know"/undecided category in the Dan Jones poll would also not have qualified for delegates, distributing that fraction to other candidates in a primary could have pushed others over the 20% qualifying threshold.

3 This polling data is being used as an example of how delegates could be allocated under these rules in Idaho and not as a forecast of the outcome in the Gem state primary.

This is part twenty-two of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

IDAHO

Election type: primary

Date: March 8

Number of delegates: 32 [23 at-large, 6 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 20% (statewide)

2012: proportional caucus

--

Changes since 2012

The date is much the same -- it amounts to the same first Tuesday after the first Monday in March date -- but the mode of delegate allocation is different in Idaho in 2016 than was the case in 2012. Republicans in the Gem state traded in their early caucus for an earlier presidential primary (moved from the traditional mid-May point where it was consolidated with the primaries for other offices).

Idaho Republicans also switched out some funky caucus allocation rules for a set of rules that is more in the mainstream of how other states are allocating delegates in 2016. Gone is the more or less instant runoff method that netted Mitt Romney a winner-take-all allocation. That has been replaced by a proportional allocation based on the statewide results of the March 8 presidential primary in Idaho. As has been witnessed in other states, though, what constitutes proportionality varies quite widely.

Thresholds

Much of that variation in the application of proportionality is attributable to a couple of factors. First, is the delegation pooled or separated for the purposes of allocation? The former typically means that a state will end up closer to a true proportional allocation of delegates than not. The latter opens the door to the bulk of the wild delegate allocation plans out there. Secondly, however, is there a threshold that the candidates must meet to qualify for delegates? With a threshold comes limitations in terms of how many candidates end up with delegates.

But that fact is tempered by the distinction raised in the first question. States that have separated allocation -- distinctions made between the allocation of at-large and congressional district delegates -- and a threshold have been the most complex. Many of the SEC primary states fit this description. Idaho fits somewhere in between states with that type of allocation and those with a proportional allocation of pooled delegates without a threshold.

It is that kind of allocation that ends up being perhaps the least complex. For example, then, Idaho Republicans will pool all of their delegates rather than invite complexity through a separate allocation of at-large delegates and the six delegates in just two congressional districts. The rationale is similar to the that of other small states. Power comes through allocating a small bloc (or blocs) of delegates rather than a much more decentralized proportional allocation.

Gem state Republicans will accomplish this through pooling their delegates but also by layering in a couple of thresholds. First, to qualify for any of the 32 delegates, a candidate must win at least 20% of the vote (before rounding) in the Idaho presidential primary. That will have the effect of limiting the number of candidates who receive delegates to likely four or fewer. If no candidate clears the 20% threshold, then the allocation would be carried out as if there was no threshold at all.

Not expressly prohibited by the rules is a backdoor to a winner-take-all allocation. While the "if no candidates clear the threshold" contingency is described, the "if only one candidate clears that qualifying threshold" is not. What that means is that there is a backdoor winner-take-all option on the table in Idaho. And since the delegates -- all 32 of them including the automatic delegates -- are pooled Idaho is the one state before March 15 where just one candidate surpassing the qualifying threshold could net that candidate all of the delegates from that state. The others to this point on the calendar that have allowed for a backdoor winner-take-all option, but the allocation was split into statewide/at-large and congressional district delegates. That makes Idaho a potentially powerful, pre-March 15 piece in the allocation puzzle. Things would have to fall right -- a crowded field with little winnowing or separation between the candidates, for example -- but a potential +32 coming out of Idaho could be more valuable to a campaign than a split of, say, the 155 delegates in Texas.

Finally, Idaho also has a true winner-take-all trigger as well. Should one candidate win a majority of the vote statewide, that candidate would also be entitled to all of the delegates from the state. This may or may not be likely in a less crowded field. The last two winners in Idaho received more than 50% of the vote.1

Delegate allocation (at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates)

The Idaho Republican delegates will be proportionally allocated to candidates based on the outcome of the March 8 primary in the Gem state. Based on the last poll conducted on the race in Idaho (the late August 2015 Dan Jones and Associates survey2), the allocation would look something like this3:

- Trump (28%) -- 32 delegates

- Carson (15%) -- 0 delegates

- Bush (7%) -- 0 delegates

- Cruz (7%) -- 0 delegates

- Rubio (6%) -- 0 delegates

- Paul (5%) -- 0 delegates

- Christie (4%) -- 0 delegates

- Fiorina (3%) -- 0 delegates

- Kasich (2%) -- 0 delegates

The arrival at such an outcome is a bit unconventional in Idaho. The allocation calculation calls for the candidate's share of the vote to be divided by the total statewide vote. That would mean that Trump, in the above example, would only receive a 28% share -- or 9 -- of the total number of delegates. That is not winner-take-all by any account. However, the rules also call for the unallocated delegates -- those not allocated to Trump above -- to "be apportioned proportionally among candidates who clear the 20 percent threshold." That would award the remaining 23 delegates to Trump, giving him the full allotment of delegates.

Were the backdoor winner-take-all allocation trigger not tripped multiple candidates crossed the 20% barrier -- or none did -- the Idaho Republican Party rules are not clear on how the rounding would be handled (though the allocation would be proportional without any threshold). The only reference to rounding is that a candidate must have 20% of the vote to qualify. 19.9%, for instance, would not round up to 20% and qualify any such candidate for delegates.

It is not clear, then, if the rounding is always up to the next whole number or simply to the nearest whole number. Additionally, there is no outline for a sequence to the rounding procedure or a contingency for unallocated or over-allocated delegates. That contingency coming into play is a function of how many candidates clear the threshold. Anything more than two candidates raises the likelihood that there will be an under- or over-allocated delegate.

If, however, the threshold is lowered to 15% to include Ben Carson in the allocation, then Trump would round up to 9 delegates, Carson would round up to 5 and the remaining 18 delegates would be uncommitted. That is due to the allocation equation laid out in the Idaho Republican Party rules. Only candidates over the threshold qualify for delegates, but a candidate claims delegates based on their share of the statewide vote divided by the total statewide vote for all candidates, not just the qualifying candidates. If the threshold is lowered to 7% to pull in Bush and Cruz, then Trump and Carson would be allocated the same 9 and 5 delegates respectively and Bush and Cruz would both round down to 2 delegates each. 14 delegates would be unallocated and would remain uncommitted. While the rounding in Idaho retains some operational question marks, the combination of simple rounding rules -- rounding up above .5 and down below it -- and not allocating delegates for those under the 20% threshold simplifies things to some degree.

Binding

Though the party rules use pledged rather than bound, the intent is the same with regard to how the Idaho delegates act at the national convention. Delegates are bound to the candidate who "proposed them on their list" or were pledged to by the Idaho Republican Party Nominating Committee on the first ballot of the roll call voting at the national convention. Like Hawaii, the candidates have some say in who their Idaho delegates will be. Candidates submit a list delegate candidates -- a slate essentially -- equal to 80% of the total delegation (26 delegates). Should a candidate win all of the delegates and/or fail to submit a list (or the requisite fee), then the Nominating Committee would select and pledge delegates to that candidate. In the event of a winner-take-all scenario, that would mean the remaining 20% of delegate slots not covered by the 80% slate. In the case of a candidate not filing a slate, that would mean how ever many delegates allocated to that candidate. In a straight proportional allocation of the delegates, the 80% slate is likely to contain enough delegates to cover the candidate. Again, that is 26 of the 32 delegates.

It is a little quirky, but it does highlight that the candidates would mostly retain some power over who their delegates are. That has implications for the national convention should it go beyond just one vote. Most of those delegates would be more loyal to the candidate than delegates selected and bound to a particular candidate but who prefer another.

Additionally, a candidate's withdrawal from the race or suspension of their campaign makes their delegates uncommitted. This is clear if the withdrawal/suspension occurs after the selection but before the convention. In that case, the Idaho Republican Party rules clearly release the delegates. However, if the withdrawal occurs before the selection process described above, then the Nominating Committee may fill those slots with as many uncommitted delegates as the withdrawing candidate was entitled to.

--

State allocation rules are archived here.

--

1 Granted, McCain had already wrapped up the nomination by the time Idaho voted in May 2008 and Romney benefitted from the aforementioned, quirky caucus allocation rules in 2012.

2 Though the 17% of respondents who fell into the "Don't Know"/undecided category in the Dan Jones poll would also not have qualified for delegates, distributing that fraction to other candidates in a primary could have pushed others over the 20% qualifying threshold.

3 This polling data is being used as an example of how delegates could be allocated under these rules in Idaho and not as a forecast of the outcome in the Gem state primary.

Thursday, January 21, 2016

2016 Republican Delegate Allocation: HAWAII

Updated 3.9.16

This is part twenty-one of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

HAWAII

Election type: caucus

Date: March 8

Number of delegates: 19 [10 at-large, 6 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional (statewide and in congressional districts)

Threshold to qualify for delegates: No official threshold

2012: proportional caucus

--

Changes since 2012

The Hawaii Republican Party rules for delegate allocation have not changed in any meaningful way as compared to the method the party operated under in 2012. The date -- the second Tuesday in March -- is the same and though Hawaii Republicans lost one at-large delegate from 2012, it is a change of just one delegate. But the small number of delegates at stake in the March 8 Hawaii Republican caucuses will be proportionally allocated based on the caucus results at both the state and congressional district level. Rather than pooling the 16 at-large and congressional district delegates, Hawaii Republicans will allocate both types separately. At-large delegates will be proportionally allocated based on the statewide results while the congressional district delegates will be awarded based on the outcome of the caucuses in each of the islands' two congressional districts.

Thresholds

There is no threshold in the Hawaii allocation process at either the state or congressional district level to qualify for delegates. However, the rounding method used by Republicans in the Aloha state both advantages the winner/top finishers and limits the number of candidates who will likely end up being allocated any delegates (see below for an illustration of this).

Delegate allocation (at-large delegates)

The Hawaii delegates will be proportionally allocated to candidates based on the outcome of the March 8 caucuses in the Aloha state. There has been no polling in the Hawaii race, but rather than make up numbers, FHQ will base the simulated allocation below on the data from ISideWith.com.1 Based on that data, the allocation of the 13 at-large and automatic delegates would look something like this2:

All of the candidates, then, round up to the next whole number despite, for example, Carson having a remainder less than .5. That leaves just one delegate left for Rand Paul by the time the sequence gets to him. Now, the junior Kentucky senator would have been allocated one delegate anyway based on pulling in 5% of the statewide vote. However, that is not the proper way of thinking about the Hawaii allocation because of the sequential rounding. Once the sequence gets to Paul, there is just one delegate left. It would be his.

Such a sequential method when coupled with always rounding up means that while there is no official threshold in Hawaii, an unofficial one will force itself into the allocation of the at-large delegates. Some candidate will be the last to be allocated delegates in the sequence and those behind that candidate will be left out of the allocation process. In this example then, that threshold is at 5%, but again, not officially.

Four years ago, all 11 at-large delegates were allocated to the top three candidates and Newt Gingrich, despite winning more than 10% of the vote had nothing to show for it. The unofficial threshold to win any delegates, then, was higher in 2012 -- around the 19% that Ron Paul received.

The main point here is not so much this threshold idea, but rather to point out that though there is no official threshold, there are limitations to who and how many candidates receive any delegates. And it should be noted that part of that is a function too of there being so few delegates in the first place.

Delegate allocation (congressional district delegates)

The same type of principle used in the allocation of the at-large delegates impacts the congressional district delegate allocation as well. There is no threshold, but as FHQ has said numerous times, there are only so many ways to proportionally allocate the three delegates the RNC apportions to each of a state's congressional districts.

The key to the allocation of the Hawaii congressional district delegates is in the rounding. Just as above, fractional delegates will be rounded up to the nearest whole number. If a candidate receives more than one-third of the vote in a congressional district, then that candidate will round up to two delegates in that district. The remaining delegate would be left to the candidate in second place in that district. If no candidate clears that 33.3% threshold in a congressional district, however, then the top three candidates would all be allocated one delegate.

This is a firmer threshold than the one discussed in the at-large example above. It is akin to some of the winner-take-all thresholds that exist in other states, but this one is specific to the allocation of two versus one delegate to the congressional district winner. To receive all three delegates -- to round up to all of them in a congressional district -- a winner would have to clear the roughly 67% barrier. That seems unlikely even with a winnowed field.

Delegate allocation

(automatic delegates)

Due to the new guidance from the RNC on the allocation and binding of the three automatic delegates, the Hawaii Republican Party could no longer leave them unbound. Rather than included them in the at-large pool of delegates as other states have done, the HIGOP has opted to separately allocated those three delegates based on the statewide results.

Given the above data from the simulation, Trump would receive two delegates and Rubio one.

Binding

Hawaii Republican delegates are bound by party rule Section 216 to candidates on the first roll call ballot at the national convention. However, those same party rules allow the candidates/campaigns some discretion in the delegate selection process. Delegates, then, may not be bound after the first ballot, but would likely remain loyal to their candidate in any subsequent vote. They would be pledged but not bound unless or until their candidate pulls his or her name from consideration.

--

State allocation rules are archived here.

--

1 I have no idea about the methodology at ISideWith. Again, this is just an exercise in how the allocation might look, but probably will not. Using their numbers is perhaps marginally better than me creating results. And yes, they sum to 102.

2 This data is being used as an example of how delegates could be allocated under these rules in Hawaii and not as a forecast of the outcome in the Aloha state caucuses.

This is part twenty-one of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

HAWAII

Election type: caucus

Date: March 8

Number of delegates: 19 [10 at-large, 6 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional (statewide and in congressional districts)

Threshold to qualify for delegates: No official threshold

2012: proportional caucus

--

Changes since 2012

The Hawaii Republican Party rules for delegate allocation have not changed in any meaningful way as compared to the method the party operated under in 2012. The date -- the second Tuesday in March -- is the same and though Hawaii Republicans lost one at-large delegate from 2012, it is a change of just one delegate. But the small number of delegates at stake in the March 8 Hawaii Republican caucuses will be proportionally allocated based on the caucus results at both the state and congressional district level. Rather than pooling the 16 at-large and congressional district delegates, Hawaii Republicans will allocate both types separately. At-large delegates will be proportionally allocated based on the statewide results while the congressional district delegates will be awarded based on the outcome of the caucuses in each of the islands' two congressional districts.

Thresholds

There is no threshold in the Hawaii allocation process at either the state or congressional district level to qualify for delegates. However, the rounding method used by Republicans in the Aloha state both advantages the winner/top finishers and limits the number of candidates who will likely end up being allocated any delegates (see below for an illustration of this).

Delegate allocation (at-large delegates)

The Hawaii delegates will be proportionally allocated to candidates based on the outcome of the March 8 caucuses in the Aloha state. There has been no polling in the Hawaii race, but rather than make up numbers, FHQ will base the simulated allocation below on the data from ISideWith.com.1 Based on that data, the allocation of the 13 at-large and automatic delegates would look something like this2:

- Trump (44%) -- 4.4 delegates [5 delegates]

- Rubio (15%) -- 1.5 delegates [2 delegates]

- Cruz (14%) -- 1.4 delegates [2 delegates]

- Carson (10%) -- 1.0 delegates [1 delegate]

- Paul (5%) -- 0 delegates

- Bush (5%) -- 0 delegates

- Christie (4%) -- 0 delegates

- Fiorina (3%) -- 0 delegates

- Kasich (2%) -- 0 delegates

All of the candidates, then, round up to the next whole number despite, for example, Carson having a remainder less than .5. That leaves just one delegate left for Rand Paul by the time the sequence gets to him. Now, the junior Kentucky senator would have been allocated one delegate anyway based on pulling in 5% of the statewide vote. However, that is not the proper way of thinking about the Hawaii allocation because of the sequential rounding. Once the sequence gets to Paul, there is just one delegate left. It would be his.

Such a sequential method when coupled with always rounding up means that while there is no official threshold in Hawaii, an unofficial one will force itself into the allocation of the at-large delegates. Some candidate will be the last to be allocated delegates in the sequence and those behind that candidate will be left out of the allocation process. In this example then, that threshold is at 5%, but again, not officially.

Four years ago, all 11 at-large delegates were allocated to the top three candidates and Newt Gingrich, despite winning more than 10% of the vote had nothing to show for it. The unofficial threshold to win any delegates, then, was higher in 2012 -- around the 19% that Ron Paul received.

The main point here is not so much this threshold idea, but rather to point out that though there is no official threshold, there are limitations to who and how many candidates receive any delegates. And it should be noted that part of that is a function too of there being so few delegates in the first place.

Delegate allocation (congressional district delegates)

The same type of principle used in the allocation of the at-large delegates impacts the congressional district delegate allocation as well. There is no threshold, but as FHQ has said numerous times, there are only so many ways to proportionally allocate the three delegates the RNC apportions to each of a state's congressional districts.

The key to the allocation of the Hawaii congressional district delegates is in the rounding. Just as above, fractional delegates will be rounded up to the nearest whole number. If a candidate receives more than one-third of the vote in a congressional district, then that candidate will round up to two delegates in that district. The remaining delegate would be left to the candidate in second place in that district. If no candidate clears that 33.3% threshold in a congressional district, however, then the top three candidates would all be allocated one delegate.

This is a firmer threshold than the one discussed in the at-large example above. It is akin to some of the winner-take-all thresholds that exist in other states, but this one is specific to the allocation of two versus one delegate to the congressional district winner. To receive all three delegates -- to round up to all of them in a congressional district -- a winner would have to clear the roughly 67% barrier. That seems unlikely even with a winnowed field.

Delegate allocation

Due to the new guidance from the RNC on the allocation and binding of the three automatic delegates, the Hawaii Republican Party could no longer leave them unbound. Rather than included them in the at-large pool of delegates as other states have done, the HIGOP has opted to separately allocated those three delegates based on the statewide results.

Given the above data from the simulation, Trump would receive two delegates and Rubio one.

Binding

Hawaii Republican delegates are bound by party rule Section 216 to candidates on the first roll call ballot at the national convention. However, those same party rules allow the candidates/campaigns some discretion in the delegate selection process. Delegates, then, may not be bound after the first ballot, but would likely remain loyal to their candidate in any subsequent vote. They would be pledged but not bound unless or until their candidate pulls his or her name from consideration.

--

State allocation rules are archived here.

--

1 I have no idea about the methodology at ISideWith. Again, this is just an exercise in how the allocation might look, but probably will not. Using their numbers is perhaps marginally better than me creating results. And yes, they sum to 102.

2 This data is being used as an example of how delegates could be allocated under these rules in Hawaii and not as a forecast of the outcome in the Aloha state caucuses.

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

2016 Republican Delegate Allocation: LOUISIANA

Updated 3.5.16

This is part twenty of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

LOUISIANA

Election type: primary

Date: March 5

Number of delegates: 46 [25 at-large, 18 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 20%1

2012: primary/caucus

--

Changes since 2012

Digging down, there are a number of changes to the Louisiana Republican Party delegate allocation rules for 2016. First, the state legislature in the Pelican state moved the presidential primary up a couple of weeks to early March back in 2014. That shift preceded the regional push to form the SEC primary. Still, the Louisiana presidential primary will fall just a few days later, the weekend after a number of southern states hold contests on March 1.

Secondly, delegates will be more clearly allocated through the presidential primary election. Four years ago, the at-large delegates were allocated based on the statewide vote in the primary while the congressional district delegates remained officially unbound (after having been selected in district caucuses). Unlike four years ago, then, Louisiana Republicans have linked the allocation of delegates -- both at-large and congressional district -- to the results of the presidential primary. There are still district caucuses, but the voting there will in part select the delegates ultimately allocated and bound to candidates based on the primary results.

Thresholds

Another change is in the qualifying threshold. In 2012, a candidate had to receive 25% of the statewide vote to qualify for any of the at-large delegates at stake in Louisiana. For 2016, just 20% is necessary. That is the maximum qualifying threshold allowed by the RNC. [Truth be told, that was true in 2012 as well. Louisiana exceeded it.]

As has been witnessed in other states, that 20% barrier has a limiting effect on who and how many candidates actually qualify for delegates. In a crowded field, fewer candidates would likely cross the line. As the field winnows, however, that number increases, but only to a point. Only as many as five candidates could qualify and that is only in the event that all five tie at the top with exactly 20%. In other words, somewhere between one and four candidates are likely to be allocated any of the at-large delegates.

There is no similar threshold conditioning the allocation of congressional district delegates. Unless one candidate runs away from the rest in a congressional district, then functionally, the top three finishers in a district vote will be allocated one delegate each.

Additionally, Louisiana Republicans have not put a winner-take-all threshold in place. Even if a candidate were to win a majority of the vote either statewide or on the congressional district level, it would not trigger an allocation of all of the (unit-specific) delegates to that candidate. It is always proportional (by RNC rules) with some caveats.

Delegate allocation (at-large and automatic delegates)

The Louisiana delegates will be proportionally allocated to candidates based on the outcome of the March 5 primary in the Pelican state. Based on an earlier poll conducted on the race in Louisiana (the late September 2015 WWL-TV/Clarus survey), the allocation would look something like this2:

Appearance, however, might not match reality here because there is a lot left unsaid in the Louisiana delegate allocation rules. Yes, a candidate must receive at least 20% of the statewide vote to qualify for any of the 28 at-large and automatic delegates. Yet, the above simulated allocation -- a backdoor winner-take-all scenario statewide -- is not be how the allocation works in practice.

There is no contingency specified in the event that only one candidate surpasses the threshold.3 And that, in turn, leaves some of this to interpretation. The way FHQ has treated other states in similar situations is that if only one candidate clears the threshold, then that candidate claims all of those delegates -- either at-large and/or congressional district -- unless explicitly prohibited by the state party rules.

Well, there is no such prohibition in Louisiana. In fact, the language of the rule is pretty important here (Rule 4c).

The catch is that the Louisiana Republican Party Executive Committee has the ambiguous discretion of rounding the delegate totals. That and the above fact about raw percentages matter whether there is just one candidate above the 20% qualifying threshold or multiple candidates (as is likely the case with a March 5 contest). Without adjusting the denominator in the allocation equation from the total votes cast to just the votes of the qualifying candidates, the Louisiana Republican Party has quietly and within the RNC rules, mind you, created a group of unbound delegates.

In the above example, Carson would get 6 or 7 at-large delegates depending on how the Executive Committee rounds that 6.44. Again, the committee has the latitude to set that allocation. But it is based on the "same proportion" of the vote that Carson received statewide. That leaves 21 or 22 unallocated delegates. Those would theoretically be delegates selected and sent to the national convention unbound (but not necessarily unpledged).

Now, that leaves a couple of items to note. First, this is quite reminiscent of the 2012 Louisiana delegate allocation rules with regard to at-large delegates. The congressional district delegates were unbound in Louisiana four years ago. But second, there likely will not be such a large number of unallocated delegates. Again, by March 5 there is likely to have been some winnowing of the field. With that shrinking of the field, the chances of a smaller group of candidates qualifying for delegates -- more than one but fewer than five -- increases.

But even if that threshold is relaxed to 10% -- so that both Trump and Bush, using the polling data above, qualify for delegates -- the three of them only add to 52% of the vote. That means that, depending on the rounding by the LAGOP Executive Committee, approximately 48% of the at-large delegates (13 delegates of 28) would be unallocated to candidates and thus unbound for the national convention.

Is that hugely consequential? In the grand scheme of things -- the race to 1237 -- probably not. However, this is yet another little wildcard to file away for when the process gets to Louisiana. But the bottom line is that this seemingly was a move by the Louisiana Republican Party to comply with the RNC rules, but retain something similar to the way the party had allocated delegates in the past. Then again, perhaps LAGOP was not that sophisticated.

Delegate allocation (congressional district delegates)

Where the state party lost some discretion on that score is in the allocation of congressional district delegates. Four years ago, those delegates were elected in congressional district caucuses and were left unbound heading into the national convention in Tampa. For 2016, those delegates will selected at the state convention based on the results of the March 5 primary in each of the six congressional districts in the Pelican state.

The same 20% threshold to qualify for at-large delegates does not apply to the allocation of congressional district delegates. Instead, there is no qualifying threshold. Again, as has been mentioned elsewhere, there are only so many ways to proportionally allocate three congressional district delegates. Even with no threshold, then, this type of allocation tends to function as if it was a top three system: the top three candidates all are allocated one delegate. The exception is if one candidate wins a majority of the vote within a congressional district. In that case, such a candidate would round up and qualify for two delegates.4 Whether a candidate reaches that majority threshold, though, greatly depends on the extent to which the field has winnowed ahead of the Louisiana primary.

Binding

At-large and congressional district delegates who are bound to candidates will be bound to them only on the first ballot of the roll call nomination vote in Cleveland (see Rule 4f). Furthermore, delegates of candidates who have suspended their campaign are no longer bound to those candidates on that initial roll call vote.

--

State allocation rules are archived here.

--

1 The 20% threshold is used by the Louisiana Republican Party to determine which candidates qualify for the statewide, at-large delegates. Though the party rules state that there are just 23 at-large delegates, citing Rule 14, there are 25 at-large delegates apportioned to the state by virtue of the RNC rules. The congressional district delegates are allocated to candidates based on the vote within those districts but with no threshold.

2 This poll is being used as an example of how delegates could be allocated under these new rules in Louisiana and not as a forecast of the outcome in the Pelican state primary.

3 More alarming, perhaps, is that there is no provision spelling out the allocation process if no candidate clears 20%.

4 That is something of a leap in reasoning considering that the rounding rules are unspecified. If the rounding is always up, regardless of the fraction, then a candidate could round up to two delegates with just a little less than 34% of the vote in a congressional district. All that is known for sure is that the Executive Committee does not explicitly have the same latitude in the rounding of congressional district delegates as it does in at-large delegates.

This is part twenty of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

LOUISIANA

Election type: primary

Date: March 5

Number of delegates: 46 [25 at-large, 18 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 20%1

2012: primary/caucus

--

Changes since 2012

Digging down, there are a number of changes to the Louisiana Republican Party delegate allocation rules for 2016. First, the state legislature in the Pelican state moved the presidential primary up a couple of weeks to early March back in 2014. That shift preceded the regional push to form the SEC primary. Still, the Louisiana presidential primary will fall just a few days later, the weekend after a number of southern states hold contests on March 1.

Secondly, delegates will be more clearly allocated through the presidential primary election. Four years ago, the at-large delegates were allocated based on the statewide vote in the primary while the congressional district delegates remained officially unbound (after having been selected in district caucuses). Unlike four years ago, then, Louisiana Republicans have linked the allocation of delegates -- both at-large and congressional district -- to the results of the presidential primary. There are still district caucuses, but the voting there will in part select the delegates ultimately allocated and bound to candidates based on the primary results.

Thresholds

Another change is in the qualifying threshold. In 2012, a candidate had to receive 25% of the statewide vote to qualify for any of the at-large delegates at stake in Louisiana. For 2016, just 20% is necessary. That is the maximum qualifying threshold allowed by the RNC. [Truth be told, that was true in 2012 as well. Louisiana exceeded it.]

As has been witnessed in other states, that 20% barrier has a limiting effect on who and how many candidates actually qualify for delegates. In a crowded field, fewer candidates would likely cross the line. As the field winnows, however, that number increases, but only to a point. Only as many as five candidates could qualify and that is only in the event that all five tie at the top with exactly 20%. In other words, somewhere between one and four candidates are likely to be allocated any of the at-large delegates.

There is no similar threshold conditioning the allocation of congressional district delegates. Unless one candidate runs away from the rest in a congressional district, then functionally, the top three finishers in a district vote will be allocated one delegate each.

Additionally, Louisiana Republicans have not put a winner-take-all threshold in place. Even if a candidate were to win a majority of the vote either statewide or on the congressional district level, it would not trigger an allocation of all of the (unit-specific) delegates to that candidate. It is always proportional (by RNC rules) with some caveats.

Delegate allocation (at-large and automatic delegates)

The Louisiana delegates will be proportionally allocated to candidates based on the outcome of the March 5 primary in the Pelican state. Based on an earlier poll conducted on the race in Louisiana (the late September 2015 WWL-TV/Clarus survey), the allocation would look something like this2:

- Carson (23%) -- 28 delegates

- Trump (19%) -- 0 delegates

- Bush (10%) -- 0 delegates

- Rubio (9%) -- 0 delegates

- Fiorina (7%) -- 0 delegates

- Cruz (6%) -- 0 delegates

- Huckabee (4%) -- 0 delegates

- Jindal (3%) -- 0 delegates

- Kasich (3%) -- 0 delegates

- Christie (2%) -- 0 delegates

Appearance, however, might not match reality here because there is a lot left unsaid in the Louisiana delegate allocation rules. Yes, a candidate must receive at least 20% of the statewide vote to qualify for any of the 28 at-large and automatic delegates. Yet, the above simulated allocation -- a backdoor winner-take-all scenario statewide -- is not be how the allocation works in practice.

There is no contingency specified in the event that only one candidate surpasses the threshold.3 And that, in turn, leaves some of this to interpretation. The way FHQ has treated other states in similar situations is that if only one candidate clears the threshold, then that candidate claims all of those delegates -- either at-large and/or congressional district -- unless explicitly prohibited by the state party rules.

Well, there is no such prohibition in Louisiana. In fact, the language of the rule is pretty important here (Rule 4c).