Add another variable to caldron already frothing at the brim on a low boil in one of 2024's biggest battlegrounds. Great Lakes state Republicans have answered the question of who will lead them into the next election cycle -- Kristina Karamo -- but that does little to answer a number of other questions that hover over the party with respect to Michigan's place in the 2024 Republican presidential nomination process.

What do Michigan Republicans do? How does the party approach 2024?

The presidential primary route

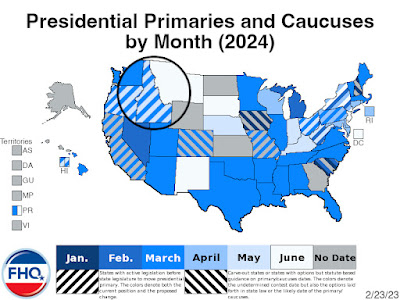

And it is not that Republicans in the Michigan legislature (or outside of it) necessarily oppose an earlier presidential primary. It was a Republican, after all, who introduced legislation in late 2022 to move the Michigan presidential primary into February,

and in passing it through the Republican-controlled state Senate, all but one member of the caucus backed the change.

That bill failed, a casualty of the end of the legislative session. But the Republican support for it then, and subsequent flip to opposition in 2023 when Democrats controlled the state government, highlight both a Republican desire to hold an earlier presidential primary and a fear of having the Republican National Committee (RNC) levy the

super penalty against state Republicans in 2024n as a consequence of going too early.

However, that does not mean that the door is closed on a Republican presidential primary in February. First, the presidential primary date change

may not even take effect in time for the 2024 cycle. Without Republican support for the legislation that shifted the primary into February, the bill was denied the supermajority it needed to take immediate effect. Unless Democrats wrap up their legislative business for the year and adjourn the 2023 session before December, then the change would not take place until

after the proposed February 27 primary date. The primary would take place on March 12 -- the second Tuesday in March -- and Republicans in the state could have a compliant presidential primary.

Second, even if Democrats in the legislature complete the session 90 days before the proposed February primary in order for the new act to take effect in 2024, it is not clear that Republicans could not have a penalty-free primary at that time. If that is what Great Lakes state Republicans want. Granted, that decision does not come down to simply what Michigan Republicans want.

Here is how that would work.

Unless, in the unlikely event that, Michigan Democrats in the legislature work with Republicans to create a second and compliant Republican presidential primary, then there will be just one presidential primary in Michigan in 2024. Assuming the primary date change does take place for 2024, then the election would fall on February 27. That is before March 1 and would, thus, conflict with RNC rules on the timing of delegate selection events. In turn, that would seemingly trigger the super penalty and cost Michigan Republicans more than three-quarters of their national convention delegates, a fact Republican legislators have offered as justification for their opposition to the date change.

Michigan Republicans begin to

resemble New Hampshire Democrats in that scenario: a party stuck between a primary scheduled by the opposing party and national party rules that would penalize them for utilizing the only option available to it. But those same RNC rules that would penalize a party for using a rogue primary also provide state parties conflicted in such ways with an out.

Under RNC Rule 16(a)(1), "[a]ny statewide presidential preference vote that permits a choice among candidates for the Republican nomination for President of the United States in a primary, caucuses, or a state convention must be used to allocate and bind the state’s delegation to the national convention..."

This was the

provision added to the RNC rules ahead of the 2016 cycle to tamp down on the number of states that in

2012 had either non-binding caucuses or beauty contest primaries that preceded caucuses that were then used to allocate national convention delegates in the presidential nomination race. All states and territories have complied with that rule since it was added. This Michigan situation would be the first to test it if the state party was forced to hold caucuses to avoid national party penalties. But holding caucuses would necessarily have to fall after the point on the calendar where the Michigan presidential primary would be scheduled in order to comply with the RNC rules on timing. Yet, statewide votes on presidential preference

must be used to bind and allocate delegates.

See the conundrum?

Michigan Republicans would end up stuck in sort of feedback loop: forced to use a primary's statewide presidential preference vote to allocate and bind delegates, but one scheduled by Democrats in the state at a point on the calendar that would dock Michigan Republicans some of those delegates for violating RNC rules on timing. Of course, there is a rule for that, Rule 16(f)(4):

The Republican National Committee may grant a waiver to a state Republican Party from the provisions of Rule Nos. 16(a)(1) and (2) where compliance is impossible and the Republican National Committee determines that granting such waiver is in the best interests of the Republican Party.

So, if Michigan Republicans wanted to use the February 27 primary and the RNC determined that that was in the best interests of the party, then a waiver could be granted. And it could be in the best interests of the party for there to be a primary in a battleground state that would likely draw more interest from and energize more voters than any alternative caucus/convention process. That is part of the same rationale that led the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee to reconsider the early primary calendar lineup for the 2024 cycle.

That is noteworthy.

Michigan Republicans could potentially use a February 27 presidential primary and NOT be penalized by the RNC. Republicans in state government have done everything in their power so far to prevent majority Democrats from making the change to the presidential primary date and have lobbied to no avail (to this point) for a second, compliant presidential primary for Republicans. Compliance, if the primary is the preferred allocation route for Michigan Republicans, is impossible. A waiver to avoid penalties is not.

The caucuses route

But what if Michigan Republicans determine that they do not want to use the primary? What if, despite everything described above, the Michigan Republican Party prefers to utilize a caucus/convention system as its means of allocating and binding delegates to the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee?

But again, that option is not directly available in Michigan. What

is available to party chairs is the ability to influence which candidates are on the primary ballot. There is a filing process for candidates who want to participate in a Michigan presidential primary, but it is an atypical one. That is because the secretary of state holds the power to determine who has access to the ballot

based on who is mentioned in news media. State party chairs, under the same provision, add their input on the matter as well, augmenting the secretary's list of candidates with a list of their own. Any other candidates who does not end up on either of those lists

can file in a manner that is more consistent with the processes in other states.

The chair's list is the mechanism Michigan Republicans could use to try to informally opt-out of the presidential primary. However, it is not clear that the state party chair merely providing no list or even suggesting to the secretary of state that there is no need for a list (because of the party using caucuses) can effectively opt Michigan Republicans out of the primary. Section 3 of the main presidential primary law says that a "statewide presidential primary shall be conducted..." That provides little wiggle room for the state party.

Barring that or the addition of an opt-out (from majority Democrats in the state legislature who may not be interested in providing one), the courts may be the only clear path toward a caucus for the Michigan Republican Party. While the courts do not provide parties with full and unfettered power to determine the processes by which they nominate candidates, the do often provide very wide latitude to the parties when conflicts arise with state law.

But why go to the courts at all? After all, the Republican National Committee determines the rules and processes that guide their presidential nomination process. But it is the conflict in those rules -- again, that feedback loop mentioned above -- that theoretically would push the Michigan Republican Party to turn to the courts in order to get out of the presidential primary and avoid a violation to Rule 16(a)(1) of the Rules of the Republican Party. It is that statewide presidential preference vote in the presidential primary, one mandated by Michigan state law, falling before any compliant caucus on or after March 1 that gums up the works.

Part of the intention of the addition of Rule 16(a)(1) was geared toward preventing states from doing what Missouri

accidentally did in 2012: hold a non-binding and noncompliant primary in February with compliant caucuses to allocate and select delegates in March. Michigan Republicans would fall into that very same trap. Only, in 2024 there is a rule in place preventing that, unlike in 2012.

The RNC cannot change that rule now. But it could grant Michigan Republicans a waiver under Rule 16(f)(4) to hold caucuses in much the same way that they could to exempt a February primary from sanctions. ...as long as it is, by rule, in the best interests of the party.

But what

is in the best interests of the party in this instance? It seems likely that the RNC will have to grant a waiver in the Michigan case regardless. But is one way -- the caucus or the primary -- more clearly in the best interests of the party than the other? The traditional approach of the Republican National Committee over time has been to provide state parties with as much latitude as possible in determining the process by which they allocate and select delegates. As one RNC member once told FHQ, "Let them [the state parties] deal with it." But that has changed. In recent cycles the national party has moved to codify rules that

restrict certain methods of delegate allocation during particular times on the primary calendar or to

bind them at the convention.

So the RNC has shown some propensity to wade into that thicket if only on a limited scale. But is the party willing to force the hand of Michigan Republicans one way or the other? Toward or away from a primary or caucus? Does it have a need to?

On the one hand, the RNC, like the Democratic National Committee (DNC), likely sees some value in the more participatory nature of the primary process. More voters drawn to participate in a competitive Republican presidential primary produces more voters energized to come back and pull the lever for Republicans in the general election. Motivating Democratic voters in battleground state primaries was, again, part of what prompted the DNC to push not only primaries over caucuses but to push battleground states into the early window of the presidential primary calendar as well. And Michigan fits the bill on that front for Republicans as well.

Yet, on the other hand, does the RNC want to be or appear heavy-handed on the matter with a state party that may or may not want to allocate, select and bind delegates through a caucus/convention process instead of a primary? There was talk among Republicans in 2018 of an

incentive to nudge states away from caucuses and toward primaries. Nothing came of it but the idea was out there at the national party level. Incentives, however, are different from granting a waiver to a state party based on which method of delegate allocation the national party deems in its best interests.

And that is where the election of a new Republican state party chair in Michigan comes into the picture.

A new state party chair and Michigan in 2024

What does the Michigan Republican Party under Kristina Karamo want to do with respect to the 2024 presidential nomination process in the Great Lakes state? How does the party want to allocate and select delegates? Where any delegate selection event ends up on the calendar will potentially limit the possibilities -- true winner-take-all allocation schemes are banned before March 15 under RNC rules -- but beyond that is what mode of allocation the state party prefers. Primary or caucus?

Given that the Michigan Republican Party advanced two chair candidates -- Karamo and Matthew DePerno -- who both ran and lost statewide in 2022 and questioned those results, the party may have a preference to avoid a state-run primary contest in 2024, especially one run by Democrats at the top. The ledger is stacked on that one side:

- state-run primary, the results of which could be called into question by Republicans -- X

- a process run by Democrats at the top -- X

- a contest too early under RNC rules that will draw severe penalties -- X

That is a strong case for Michigan Republicans opting out of a noncompliant primary and choose to select and allocate national convention delegates based on a caucus/convention system in 2024.

Obviously, however, it is more complicated than merely opting out of the primary, as has been highlighted above.

And again, is opting out something that is in the best interests of the Republican Party (as determined by the national party)? Recall also that either way -- primary or caucus -- it is likely that the RNC will have to issue a waiver.

Even that RNC waiver decision is fraught with complexities. Think about the decision-making environment in that scenario. For staters, the RNC has

once again publicly stated that it

intends to remain neutral in the 2024 presidential nomination race. But any decision in this Michigan situation could be viewed as putting a thumb on the scales. The argument is out there that

a caucus would potentially help Trump. Maybe, but the

former president's endorsement failed to carry DePerno over the finish line in the race for chair. Perhaps, then, Trump's reach is less than it once was.

Still, perception may become reality in this case. If the RNC actively grants a waiver for Michigan Republicans to hold caucuses, then that could be viewed as helping Trump, as not being neutral. And that may even be true in the event that the RNC passively stands by and allows the Michigan Republican Party to fight it out -- potentially in court -- with the state to opt out of the primary. The no waiver path.

The flip side carries problems of its own. If the caucuses are viewed as helping Trump, does the national party nudging Michigan Republicans toward using the primary (via a waiver) instead end up being viewed as hurting Trump? It is not clear that that would necessarily be the case, but a candidate Trump attempting to (re)burnish his antiestablishment credibility may be inclined to raise the issue.

From the RNC's perspective, there are some additional downstream considerations now that a new chair is in place for the state party in Michigan. Again, there are those participatory aspects in a general election battleground that may motivate the national party to advocate for the primary; to issue a waiver in the case of the primary only.

That may be a route that saves the state party from itself. Under Karamo, the party may wish to circumvent a state-run process, one run by Democrats, but a caucus/convention process -- or even a party-run primary, if the state party were to go down that road -- would cost the party money. That is money that could be better spent building the state party and laying the groundwork for a fall general election. That may or may not outweigh any misgivings about election integrity from Republicans in the state. Additionally, the state party chair vote

was not exactly a smooth one. Now, that does not mean that it was a sign of things to come in any future caucuses with presidential delegates on the line, but it does not, perhaps, inspire confidence at the national party level.

The case of 1988 (or was that 1986?)

It is not as if Michigan Republicans have not been down this road before.

For the 1988 cycle, the state party was inventive in how it selected and allocated delegates in the presidential nomination contest. Then as now, the name of the game on the state level was trying to draw candidate and media attention and impact the course of the presidential nomination race. Only, instead of trying to establish and move around a presidential primary, the party chose instead to conduct a

long caucus/convention process that

began in the late summer of 1986.

It was the ultimate insiders game, and that battle among Bush, Kemp and Robertson delegates happened prior to the Iowa caucuses in 1988.

To be clear, it is not assured that a 2024 caucus/convention process would follow that same route. At the very least, the dividing lines are not so clearly demarcated now as then when establishment forces were aligned against the upstart ideological push from Robertson and the Christian Coalition. As the recent chair's election showcased, the battle in the Michigan Republican Party was among a cadre of candidates who were all firmly in the Trump wing of the party. But are there divides therein? In the broader party, perhaps. There is already an

effort among Republican legislators to draft Ron DeSantis.

But look, none of that means that history will repeat itself in Michigan in 2024. But if one is in the RNC, a group who may have to have a hand in the primary or caucus decision in Michigan, then a broader vote in a primary may be a safer route than allowing the flames of division to be stoked in the crucible of a state party-run caucus/convention system. That waiver decision, if it is for a primary, is not one without costs for the RNC, but it may be in the best interests of the party in a likely 2024 general election battleground.

--

See more on our political/electoral consulting venture at FHQ Strategies.