One electoral reform that FHQ has touched on in the past and has increasingly popped up on the presidential primary radar is ranked choice voting (RCV). And let us be clear, while the idea has worked its way into state-level legislation and state party delegate selection plans, widespread adoption of the practice is not yet at hand.

However, there has been some RCV experimentation on a modest scale in the delegate allocation process primarily in small states. And that has opened the door to its consideration in a broader swath of states across the country. States, whether state parties or state legislators, are seeing some value in allowing for a redistribution of votes based on a voter's preferences to insure, in the case of presidential primaries, that every voter has a more direct say in the resulting delegate allocation.

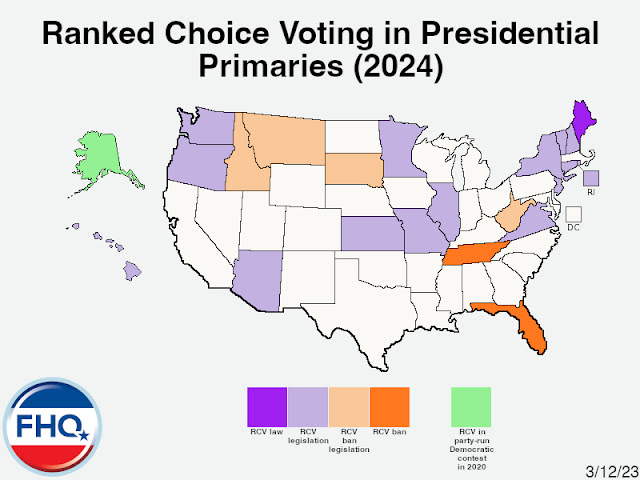

That is apparent in legislation that has been proposed in state legislatures across the country as they have begun convening their 2023 sessions. Again, RCV is not sweeping the nation, as the map below of current legislation to institute the method in the presidential nomination process will attest. There are a lot of unshaded states. But if RCV was adopted across those states where it has been passed (Maine), where it has been used in Democratic state party-run processes (Alaska, Kansas and North Dakota), and where it is being considered by legislators in 2023 then it would affect the allocation of nearly a third of Democratic delegates and a little more than a quarter of Republican delegates. That is not nothing.

The thrust of activity on adding RCV to presidential primaries for 2024 in legislatures across the country has shifted since FHQ last updated the situation in April. While much of the first few months of the 2023 state legislative sessions were about introducing legislation, the time since has mostly been about moving that legislation, and in recent days, doing so before legislatures adjourn.

Unlike much of April, however, there were a few new bills proposed since the last update. A pair of companion bills in both chambers of the New Jersey legislature were introduced to establish RCV in presidential primaries and for the election of electors to the Electoral College. In Colorado, a measure to set up RCV for the 2028 cycle quickly came and went. SB 301 was proposed in late April and went nowhere before the legislature in the Centennial state adjourned for the year earlier this month. And just this last week, a trio of New York Republican members of the US House introduced legislation to prohibit the use of RCV in elections to federal offices. It is not clear whether that extends to the nomination phase as well. But not much is clear about the bill without text. Currently, the details are missing.

There was, however, continued progress for some of those RCV-related bills that have previously been floating around out there this session.

From 30,000 feet, the overview remains much the same. The existing pattern of legislation has been for Republican-controlled states (where legislation has been proposed) to move bans on RCV while Democratic-controlled legislatures and Democratic legislators in red states have largely been behind efforts to augment the presidential primary process with RCV. That outlook has not changed. But it has evolved to some degree. To the extent any of the RCV-related legislation has been successful, it has been more likely to move through legislatures and be signed into law in Republican-controlled states. The Montana measure to prohibit RCV that was before Governor Gianforte (R) during the last update was signed into law, for instance. It brings the Treasure state in line with other neighbors -- Idaho and South Dakota -- in banning RCV during the 2023 session.

All of that maintains the status quo as it has existed in those states. And in many ways, that -- maintaining the status quo -- is the path of least resistance with regard to RCV.

And resistance is the key word when the focus shifts to those states with active bills to institute RCV for 2024 (or beyond) in the state-run presidential nomination processes. It is not that those bills have not budged, it is that most of those bills have not easily made their way through the legislative process. Yet, most is not all. A handful of RCV measures have found some modicum of success.

In Hawaii, the differences across passed versions of the bill raised last month were squared and that measure was sent off to Governor Josh Green (D) for his consideration. But while that may bring RCV to the Aloha state, any new law will not affect state-run presidential primaries. That is because while the Hawaii legislature was able to push HB 1294 through before adjournment in early May, the bill to create a state-run presidential primary failed. However, Aloha state Democrats do intend to use RCV in their party-run primary again in 2024. Beyond that, the only other measures that moved since late April were ones in Minnesota and Oregon. HB 2004 in Oregon passed the lower chamber there and awaits action in the state Senate. And in the Land of 10,000 Lakes, an appropriation bill with a RCV rider passed the legislature and was signed into law. However, the money will be used not for implementing RCV but for the Secretary of State of Minnesota to include consideration of the process in a broader voting study.

And that is it.

The last month may have seen incremental developments, but those changes have occurred as legislatures have been adjourning. And that may be the biggest change this month. More RCV-related bills have been rendered inactive or dormant as legislatures have tagged out for the year (or for regular sessions anyway with no guarantee that RCV will be revisited). That claimed both bills that had been proposed in Vermont, for example. The Senate version passed the upper chamber, but stalled in the House and never moved before the legislature in the Green Mountain state ended its session.

The picture, then, of RCV and the 2024 presidential nomination process remains one of incremental movement at best in the first half of 2023. A handful of Republican-controlled states in the mountain West have bolstered the status quo with bans of RCV, and momentum on the pro- side has been next to negligible. There may be incremental advances where RCV is being experimented with in the presidential nomination process for 2024. But note also that most of the experimenting is being done by state parties in party-run processes on the Democratic side. And further, regardless of whether the legislation has sought to establish RCV or ban it, most of the movement has been in relatively small states. Idaho, Hawaii, Montana, South Dakota and Vermont are not the big hitters of national politics. Laboratories for or against RCV are in small states for now. And that may or may not be the best proving ground for it in the presidential nomination process (or anywhere else).

The bottom line, however, is that while RCV may be considered a remedy to some of the maladies that plague American politics, its adoption is not yet widespread. And that does not look to change much more than incrementally in 2023.

Related:

--

Recent posts: