This is part twenty-five of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

MICHIGAN

Election type: primary

Date: March 8

Number of delegates: 59 [14 at-large, 42 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 15% (statewide)1

2012: proportional primary

--

Changes since 2012

There are actually a number of changes to the Michigan method of delegate allocation for 2016 as compared to four years ago. The most consequential may be that the primary is scheduled for a compliant date this time around; a departure from the last two cycles. That non-compliance in 2008 and 2012 meant that Michigan Republicans had their national convention delegation cut in half. With a rules-compliant primary on March 8, Michigan Republicans will have a full 59 delegates in 2016, and that makes it the most delegate-rich state in between Super Tuesday I on March 1 and Super Tuesday II on March 15.

Those 59 delegates will, unlike in 2012, be pooled and all proportionally allocated to candidates who receive at least 15 percent of the vote statewide. Michigan was minimally proportional last time. The halved delegation forced the Michigan Republican Party to handle its delegate allocation in a plan that was divergent from its original rules. Rather than have three delegates apportioned to each of the Great Lakes state's 14 congressional districts, the party distributed just two to each. Those two delegates were winner-take-all to the victor within the congressional districts. But that left just two delegates -- out of the penalty-decreased 30 -- to be proportionally allocated at-large (based on the statewide results). That was consistent with the Republican National Committee rules on delegate allocation in 2012. States could allocate congressional district delegates in a winner-take-all fashion, but had to proportionally allocate at least the at-large delegates.

Only, the Michigan Republican Party did not follow that guidance from the Republican National Committee. Rather than proportionally allocate those two at-large delegates as called for by the Rules of the Republican Party, the Michigan GOP awarded them both to the winner of the statewide primary vote. That meant a couple of things. First, Michigan functioned as a winner-take-all by congressional district state in 2012, but one with a reduced delegation. The second point is that because the Michigan delegation was already cut in half due to the timing violation -- February primary -- the RNC did not have the means to penalize Michigan again for any allocation violation. The national party only had the one 50% penalty that it could dole out just once.

That decision was actually consequential as the competitive Michigan primary in 2012 should have evenly split the delegates between Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum. Each won seven congressional districts, but Romney won the primary and took the two at-large delegates, giving the former Massachusetts governor a 16-14 advantage in the Michigan delegate count.

Thresholds

None of those issue exist for 2016, though. Under the current rules, the Michigan Republican delegate allocation is made simpler by the fact that party has opted to pool all 59 delegates, regardless of at-large, congressional district or automatic distinctions, and proportionally allocate them. Only candidates who receive more than 15 percent of the statewide qualify for any of those delegates.

There are two exceptions to that 15 percent threshold. The first is under the condition that no one reaches a 15 percent share of the statewide vote. In that situation, the threshold drops to the winner's share of the vote minus five percent. If, for example, the winner receives 12.1 percent of the vote in the March 8 primary, then the threshold to qualify for delegates is 7.1 percent.2 That puts a premium on the candidates behind the winner being close to qualify for delegates. The odds of that are enhanced in that if the winner is below 15 percent statewide, then there will likely be a significant amount of clustering with a big field.

Obviously, the more the field winnows ahead of March 8, the less applicable the below-15-percent contingency becomes. Yet, that winnowing tends to raise the possibility of someone winning a majority of the vote. Should someone receive a majority of the statewide vote, that candidate is entitled to all 59 delegates.

The Michigan Republican Party rules also allow (by not specifically prohibiting) a backdoor winner-take-all option. If only one candidate clears the 15 percent threshold statewide, then that candidate would take all 59 delegates. Yet, the odds of that occurring decrease as the field of candidates narrows. Winnowing makes a tripping of the winner-take-all trigger more likely, but decreases the likelihood of a backdoor winner-take-all outcome.

Delegate allocation (at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates)

Assuming that all the remaining candidates clear the 15 percent threshold, the allocation of the pool of 59 Michigan delegates is governed by a comparatively simple set of rounding rules. If any candidate should fail to reach the qualifying threshold, then the allocation equation only counts the votes of the qualifying candidates as its denominator (rather than the total statewide vote).

Candidates who have fractional delegates of .5 and above round up and those below that threshold round down to the nearest whole number. If that rounding yields an overallocation of delegates, then the superfluous delegate is subtracted from the total of the candidate with the smallest vote share (above the qualifying threshold). In the case of some or all of the qualifying candidates having fractional delegates below the .5 threshold and a resulting under-allocation of delegates, an extra delegate will be added to the top votegetter statewide to bring the total number of delegates allocated to 59.

Binding

The rules of the Michigan Republican Party bind delegates from the state to candidates based on the presidential primary through the first ballot at the national convention. Compared to some other states, the Michigan Republican Party has a low but inclusive bar for the release of delegates. If a candidate withdraws or suspends their campaign, their delegates are released and become unbound. If that candidate endorses another candidate, any delegates allocated to them become unbound. If a candidate runs for another party's nomination or becomes the nominee of another party -- any party other than the Republican Party -- then any delegates allocated to that candidate become unbound.

In other words, it is a low unbinding trigger in Michigan.

--

State allocation rules are archived here.

--

1 If no candidate achieves a 15 percent share of the vote, then the qualifying threshold becomes the winner's share minus five percent.

2 The winner's share is rounded to the nearest one-tenth of one percent if below 15 percent and the lowered threshold equals that share minus five percent.

--

Monday, March 7, 2016

Thursday, March 3, 2016

On a Revisionist History of the 1988 Southern Super Tuesday

This overly retweeted tweet made its way into the FHQ Twitter feed yesterday, and it really strikes me as #wrong.

The idea of shifting some or all of the southern states to the front of the Democratic Party window -- the period in which the now-so-called carve-out states -- was something that was making the rounds in political circles across the South as early as the early 1970s. Jimmy Carter discussed the idea of a southern regional primary in the infancy of his initial presidential nomination bid just after he completed his stint as Georgia governor. That is not very far into the post-reform era. And it also pre-dates any Jesse Jackson run for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Carter was also tangentially involved in the positioning of the Florida presidential primary for the 1976 cycle. Legislators in the Sunshine state were going to move the Florida primary to a later date, but the Carter team worked their connections in Florida -- connections forged in his time as governor of Georgia -- to request that the primary be kept in March. That primary was a de facto southern elimination round as Carter's win there over George Wallace virtually ended Wallace's chances and further propelled Carter's run to the nomination. It goes without saying that this, too, was before Jesse Jackson's run in 1984.

Facing a prospective challenge from Ted Kennedy in 1980, the Carter White House also made similar entreaties with legislators in both Alabama and Georgia to move their primaries to coincide with the Florida primary in 1980. That was viewed by the Carter campaign as an early counterweight to perceived potential victories by Kennedy in earlier New Hampshire and Massachusetts. The picture that emerges is more of an organic build toward a southern regional primary, and, again, this was before Jesse Jackson's run.

The southern regional primary idea was still around in the lead up to 1984. Several southern states shifted to early caucuses that cycle and began to make the front end of the calendar even more southern-flavored. Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi and South Carolina Democrats all shifted their contests into March, joining Alabama, Florida and Georgia on the 1984 primary calendar. The decisions in those states also pre-dated the time period when it was clear that Jesse Jackson was going to run for the Democratic nomination that cycle.

Before the timeline even gets to 1985 when the decisions on 1988 presidential primary dates started coming out of southern state legislatures, then, there is already ample evidence that the movement toward a southern regional primary was in the works. It had happened already; organically and before Jackson.

But this is also only the tip of the iceberg for what is missed in Jilani's revisionist -- or perhaps context-less -- account of the 1988 calendar.

The notion that southern state legislators "frontloaded red states" borders on preposterous. First, the red state/blue state construct dates most specifically to the 2000 election cycle; three cycles after 1988. Southern legislators, who were overwhelmingly Democratic at the time, moved those contests for 1988 attempting to, in the aggregate, influence the nomination. Dating back to the early 1970s, the idea was that the South would speak with one voice behind a more moderate candidate who would, in their way of thinking, make those southern states Democratic in the fall general election campaign. With Jimmy Carter's 1976 run as the example, the idea was to win some southern states in the fall. To do that they needed a southern or more moderate/conservative candidate. Those were the dominoes in all of this. And that way of thinking survived to and through both of Bill Clinton's runs for the White House. During a period in which Democrats struggled to win the White House, the only success the party had in winning was in nominating a southerner who could peel off some southern states in the general election.

Yes, the Democratic Leadership Council was involved on the periphery of the effort in the lead up to 1988, but Jilani is assigning to them, and the state governments that made the decisions to shift primaries on the calendar, a level of sophistication that just did not exist at the time. His thesis is without context. If they were sophisticated enough to attempt to counter Jackson, then surely they would have realized after Jackson's success with African American voters in 1984 that they -- southern decision makers -- were actually setting Jackson up for success in the Deep South where African American voters comprised a significant portion of the Democratic primary electorate.

That level of sophistication did not exist. Southern political actors were surprised by the results in the 1988 primaries and in many states opted to drop out of the calendar coalition for 1992. Jesse Jackson may have been on the minds of those making the decisions on primary dates for 1988 in 1985-87, but he was not the motivation for moving those states up. The movement was afoot before Jackson and actually benefited him in 1988. Those states just were not "red" in the eyes of those making those decisions. The hope was that they would turn at least some of those states Democratic in the fall.

This is a pretty blatant revision of this history of how the 1988 Southern Super Tuesday came to be.Let me say it again: Frontloading the primary with red states was designed to stop Jesse Jackson pic.twitter.com/I1QyKATsVR— Zaid Jilani (@ZaidJilani) March 3, 2016

The idea of shifting some or all of the southern states to the front of the Democratic Party window -- the period in which the now-so-called carve-out states -- was something that was making the rounds in political circles across the South as early as the early 1970s. Jimmy Carter discussed the idea of a southern regional primary in the infancy of his initial presidential nomination bid just after he completed his stint as Georgia governor. That is not very far into the post-reform era. And it also pre-dates any Jesse Jackson run for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Carter was also tangentially involved in the positioning of the Florida presidential primary for the 1976 cycle. Legislators in the Sunshine state were going to move the Florida primary to a later date, but the Carter team worked their connections in Florida -- connections forged in his time as governor of Georgia -- to request that the primary be kept in March. That primary was a de facto southern elimination round as Carter's win there over George Wallace virtually ended Wallace's chances and further propelled Carter's run to the nomination. It goes without saying that this, too, was before Jesse Jackson's run in 1984.

Facing a prospective challenge from Ted Kennedy in 1980, the Carter White House also made similar entreaties with legislators in both Alabama and Georgia to move their primaries to coincide with the Florida primary in 1980. That was viewed by the Carter campaign as an early counterweight to perceived potential victories by Kennedy in earlier New Hampshire and Massachusetts. The picture that emerges is more of an organic build toward a southern regional primary, and, again, this was before Jesse Jackson's run.

The southern regional primary idea was still around in the lead up to 1984. Several southern states shifted to early caucuses that cycle and began to make the front end of the calendar even more southern-flavored. Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi and South Carolina Democrats all shifted their contests into March, joining Alabama, Florida and Georgia on the 1984 primary calendar. The decisions in those states also pre-dated the time period when it was clear that Jesse Jackson was going to run for the Democratic nomination that cycle.

Before the timeline even gets to 1985 when the decisions on 1988 presidential primary dates started coming out of southern state legislatures, then, there is already ample evidence that the movement toward a southern regional primary was in the works. It had happened already; organically and before Jackson.

But this is also only the tip of the iceberg for what is missed in Jilani's revisionist -- or perhaps context-less -- account of the 1988 calendar.

The notion that southern state legislators "frontloaded red states" borders on preposterous. First, the red state/blue state construct dates most specifically to the 2000 election cycle; three cycles after 1988. Southern legislators, who were overwhelmingly Democratic at the time, moved those contests for 1988 attempting to, in the aggregate, influence the nomination. Dating back to the early 1970s, the idea was that the South would speak with one voice behind a more moderate candidate who would, in their way of thinking, make those southern states Democratic in the fall general election campaign. With Jimmy Carter's 1976 run as the example, the idea was to win some southern states in the fall. To do that they needed a southern or more moderate/conservative candidate. Those were the dominoes in all of this. And that way of thinking survived to and through both of Bill Clinton's runs for the White House. During a period in which Democrats struggled to win the White House, the only success the party had in winning was in nominating a southerner who could peel off some southern states in the general election.

Yes, the Democratic Leadership Council was involved on the periphery of the effort in the lead up to 1988, but Jilani is assigning to them, and the state governments that made the decisions to shift primaries on the calendar, a level of sophistication that just did not exist at the time. His thesis is without context. If they were sophisticated enough to attempt to counter Jackson, then surely they would have realized after Jackson's success with African American voters in 1984 that they -- southern decision makers -- were actually setting Jackson up for success in the Deep South where African American voters comprised a significant portion of the Democratic primary electorate.

That level of sophistication did not exist. Southern political actors were surprised by the results in the 1988 primaries and in many states opted to drop out of the calendar coalition for 1992. Jesse Jackson may have been on the minds of those making the decisions on primary dates for 1988 in 1985-87, but he was not the motivation for moving those states up. The movement was afoot before Jackson and actually benefited him in 1988. Those states just were not "red" in the eyes of those making those decisions. The hope was that they would turn at least some of those states Democratic in the fall.

--

Labels:

1988 election,

primary calendar,

region (South),

Super Tuesday

Sunday, February 28, 2016

2016 Republican Delegate Allocation: MAINE

This is part twenty-four of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

MAINE

Election type: caucus

Date: March 5

Number of delegates: 23 [14 at-large, 6 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 10% (statewide)

2012: non-binding caucuses

--

Changes since 2012

Like in a number of other caucus states in 2016, the Republican Party in Maine was forced by changes in the Republican National Committee delegate selection rules to alter the standard operating procedure in the Pine Tree state. Traditionally, Maine Republicans have conducted their delegate selection process through a caucus/convention system. That is not different for 2016. However, rather than beginning the stepwise process with a non-binding preference vote, as had been the case in past cycles, Republicans in Maine will conduct precinct caucuses on March 5 with a binding straw poll.

Based on the statewide results, candidates receiving more than 10% of the vote will be proportionally allocated a shared of the 23 delegates that will comprise the Maine delegation to the Republican National Convention in Cleveland.

Thresholds

That the preference vote at the caucuses is binding on the delegate allocation is the big ticket change for Maine Republicans since 2012. Yet, that creation of a couple of thresholds dictating that allocation is also noteworthy. To qualify for any of the 23 pooled delegates -- the at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates are all one big bloc -- a candidate must receive at least ten percent of the vote. A candidate cannot receive 9.7 percent of the statewide vote, for example, and round up to the ten percent threshold. The delegates are rounded, not the percentages that determine the ultimate delegate allocation.

It seems unlikely in a winnowed field of candidates, that no one will reach 10% of the vote. There is, however, a contingency in place to lower the threshold to five percent should no one hit the ten percent mark.

Additionally, in the event that one candidate receives a majority of the statewide vote, then that candidate is entitled to all 23 of the Maine delegates. Furthermore, there are no rules in place prohibiting a backdoor to a winner-take-all allocation. Should only one candidate clear the ten percent hurdle in the statewide vote, then that candidate would be allocated all 23 delegates from the state.

Delegate allocation (at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates)

The allocation of delegates in Maine is fairly routine. Candidates who cross the ten percent threshold are eligible for a proportional share of the state's delegates. As has been the case in a number of other states -- Massachusetts comes to mind -- only the votes of those candidates over the threshold are used in determining the number of delegates each candidate receives. Any votes for candidates below the threshold are excluded from the delegate allocation equation.

In other words, the total number of qualifying votes is the denominator and the vote share for a particular candidate is the numerator. The resultant percentage is used to calculate the share of the 23 delegates that that candidate will be allocated.

This is all done in sequence from the top votegetter over the threshold to the last qualifying candidate. Any rounding of the delegates is also done as part of that sequence. That means that the statewide winner has his or her delegates calculated and rounded and then the the second place finisher and so on. This method has the effect of rounding every candidate up (or down), leaving the last qualifying candidate with the leftovers.

Such a method tends to circumvent the over- or under-allocated delegates problem that other states have as a feature of their rounding method. But it also stands as another advantage for winners (by default). It makes the last qualifying position one to be avoided since that is the last candidate in the rounding sequence. One could call that the leftovers position. Whatever label is applied, it is another built-in advantage for those at the top of the vote order (in this case, statewide).

Binding

The delegates allocated based on the results of the March 5 preference vote in caucuses across Maine will be bound to those candidates through the first ballot at the national convention. Delegates can only be released from that binding if the candidate to whom they are bound withdraws before the national convention in Cleveland. The withdrawal of a candidate from the race means that any Maine delegates allocated to them are automatically released, becoming unbound.

MAINE

Election type: caucus

Date: March 5

Number of delegates: 23 [14 at-large, 6 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 10% (statewide)

2012: non-binding caucuses

--

Changes since 2012

Like in a number of other caucus states in 2016, the Republican Party in Maine was forced by changes in the Republican National Committee delegate selection rules to alter the standard operating procedure in the Pine Tree state. Traditionally, Maine Republicans have conducted their delegate selection process through a caucus/convention system. That is not different for 2016. However, rather than beginning the stepwise process with a non-binding preference vote, as had been the case in past cycles, Republicans in Maine will conduct precinct caucuses on March 5 with a binding straw poll.

Based on the statewide results, candidates receiving more than 10% of the vote will be proportionally allocated a shared of the 23 delegates that will comprise the Maine delegation to the Republican National Convention in Cleveland.

Thresholds

That the preference vote at the caucuses is binding on the delegate allocation is the big ticket change for Maine Republicans since 2012. Yet, that creation of a couple of thresholds dictating that allocation is also noteworthy. To qualify for any of the 23 pooled delegates -- the at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates are all one big bloc -- a candidate must receive at least ten percent of the vote. A candidate cannot receive 9.7 percent of the statewide vote, for example, and round up to the ten percent threshold. The delegates are rounded, not the percentages that determine the ultimate delegate allocation.

It seems unlikely in a winnowed field of candidates, that no one will reach 10% of the vote. There is, however, a contingency in place to lower the threshold to five percent should no one hit the ten percent mark.

Additionally, in the event that one candidate receives a majority of the statewide vote, then that candidate is entitled to all 23 of the Maine delegates. Furthermore, there are no rules in place prohibiting a backdoor to a winner-take-all allocation. Should only one candidate clear the ten percent hurdle in the statewide vote, then that candidate would be allocated all 23 delegates from the state.

Delegate allocation (at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates)

The allocation of delegates in Maine is fairly routine. Candidates who cross the ten percent threshold are eligible for a proportional share of the state's delegates. As has been the case in a number of other states -- Massachusetts comes to mind -- only the votes of those candidates over the threshold are used in determining the number of delegates each candidate receives. Any votes for candidates below the threshold are excluded from the delegate allocation equation.

In other words, the total number of qualifying votes is the denominator and the vote share for a particular candidate is the numerator. The resultant percentage is used to calculate the share of the 23 delegates that that candidate will be allocated.

This is all done in sequence from the top votegetter over the threshold to the last qualifying candidate. Any rounding of the delegates is also done as part of that sequence. That means that the statewide winner has his or her delegates calculated and rounded and then the the second place finisher and so on. This method has the effect of rounding every candidate up (or down), leaving the last qualifying candidate with the leftovers.

Such a method tends to circumvent the over- or under-allocated delegates problem that other states have as a feature of their rounding method. But it also stands as another advantage for winners (by default). It makes the last qualifying position one to be avoided since that is the last candidate in the rounding sequence. One could call that the leftovers position. Whatever label is applied, it is another built-in advantage for those at the top of the vote order (in this case, statewide).

Binding

The delegates allocated based on the results of the March 5 preference vote in caucuses across Maine will be bound to those candidates through the first ballot at the national convention. Delegates can only be released from that binding if the candidate to whom they are bound withdraws before the national convention in Cleveland. The withdrawal of a candidate from the race means that any Maine delegates allocated to them are automatically released, becoming unbound.

Saturday, February 27, 2016

2016 Republican Delegate Allocation: MASSACHUSETTS

This is part twenty-three of a series of posts that will examine the Republican delegate allocation rules by state. The main goal of this exercise is to assess the rules for 2016 -- especially relative to 2012 -- in order to gauge the potential impact the changes to the rules along the winner-take-all/proportionality spectrum may have on the race for the Republican nomination. For this cycle the RNC recalibrated its rules, cutting the proportionality window in half (March 1-14), but tightening its definition of proportionality as well. While those alterations will trigger subtle changes in reaction at the state level, other rules changes -- particularly the new binding requirement placed on state parties -- will be more noticeable.

MASSACHUSETTS

Election type: primary

Date: March 1

Number of delegates: 42 [12 at-large, 27 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 5% (statewide)

2012: proportional primary

--

Changes since 2012

MASSACHUSETTS

Election type: primary

Date: March 1

Number of delegates: 42 [12 at-large, 27 congressional district, 3 automatic]

Allocation method: proportional

Threshold to qualify for delegates: 5% (statewide)

2012: proportional primary

--

Changes since 2012

The Massachusetts Republican Party did very little to alter for 2016 the delegate allocation plan the party used in 2012. As was the case four years ago, the party will pool its delegates and proportionally allocate them to candidates based on the results of the March 1 primary in the Bay state. However, unlike 2012, that pool of delegates will include not only the at-large and congressional district delegates, but the three automatic/party delegates as well. Additionally, the party has lowered its qualifying threshold from 15 percent to five percent. That likely yields delegates for all of the candidates still involved.

Thresholds

Dropping the qualifying threshold by ten percent is not a trivial change. A 15 percent threshold is much more likely to keep candidates with only very narrow paths (or no path at all) to the nomination out of the delegate count in Massachusetts. But at just five percent, the bar is considerably lower. No, that is not a boon to any candidates on the lower end of the order in the vote totals. Those candidates will only get a very small number of delegates.

The real importance of the change -- lowering the threshold -- lies in the fact that those are delegates that would have gone to candidates at the top of the order with a higher threshold. The lower hurdle means fewer delegates for the most viable candidates in the race.

The real importance of the change -- lowering the threshold -- lies in the fact that those are delegates that would have gone to candidates at the top of the order with a higher threshold. The lower hurdle means fewer delegates for the most viable candidates in the race.

Delegate allocation (at-large, congressional district and automatic delegates)

The allocation in Massachusetts is pretty simple; the simplest thing this side of a truly winner-take-all allocation. Candidates who clear the five percent threshold will qualify for a proportional share of the 42 delegates Massachusetts has to offer. That calculation will utilize the qualifying total -- the votes of just the candidates who clear the five percent barrier -- as the denominator and the candidates' shares of the vote as the numerator.

The Massachusetts GOP will then use simple rounding rules to determine the final count. Those candidates with fractional delegates more than .5 will round up to the nearest whole number. Any candidate below .5 will round down. In the event that the rounding leads to an overallocation of delegates -- more than the 42 Massachusetts has -- then those delegates will be taken from the candidate(s) at the bottom of the vote order. Should there be an under-allocation -- fewer than 42 delegates allocated after rounding -- any unallocated delegate(s) will be awarded to the top votegetters.

The Massachusetts GOP will then use simple rounding rules to determine the final count. Those candidates with fractional delegates more than .5 will round up to the nearest whole number. Any candidate below .5 will round down. In the event that the rounding leads to an overallocation of delegates -- more than the 42 Massachusetts has -- then those delegates will be taken from the candidate(s) at the bottom of the vote order. Should there be an under-allocation -- fewer than 42 delegates allocated after rounding -- any unallocated delegate(s) will be awarded to the top votegetters.

Binding

The 42 members of the Massachusetts Republican delegation will be bound to the candidates to whom they have been allocated through the first ballot of the Republican National Convention in Cleveland.

Friday, February 26, 2016

SEC Primary Delegate Number Crunch

Let's do a quick simulated delegate allocation.

Bloomberg News released a Purple Strategies survey of voters in the seven southern states that will comprise the SEC primary on March 1. These numbers may prove to be off the mark when voters head to the polls on Super Tuesday. Nonetheless, if we assume that those numbers are the vote percentages in each of the seven states -- Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia -- and their congressional districts, we can glean more than a little something from the hypothetical delegate allocation. The polling data are even more interesting in light of just how close second and third place are. Rubio and Cruz are tied at 20% each. That has some interesting implication for a simulated delegate distribution.

Before digging in, here are the assumptions of this exercise:

Here's what happens:

Observations:

Bloomberg News released a Purple Strategies survey of voters in the seven southern states that will comprise the SEC primary on March 1. These numbers may prove to be off the mark when voters head to the polls on Super Tuesday. Nonetheless, if we assume that those numbers are the vote percentages in each of the seven states -- Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia -- and their congressional districts, we can glean more than a little something from the hypothetical delegate allocation. The polling data are even more interesting in light of just how close second and third place are. Rubio and Cruz are tied at 20% each. That has some interesting implication for a simulated delegate distribution.

Before digging in, here are the assumptions of this exercise:

- The polling data are being treated as the vote shares of the candidates in the seven SEC primary states.

- That same polling data will also be treated as the vote shares of the candidates in all 75 congressional districts in the SEC primary states. [Yes, this is perhaps the assumption that asks for the largest leap of faith.]

- An exact tie between Cruz and Rubio makes this simulation a touch more difficult. That is particularly true when attempting to determine how to allocate the congressional district delegates. There are only three delegates in each of the 75 district. In the majority of these states the winner in a district gets two delegates and the runner-up receives the remaining one delegate. If Cruz and Rubio are tied, then the allocation of that runner-up delegate -- everywhere -- gets tough. For the purposes of this exercise, we will assume that Rubio received one more vote than Cruz on the congressional district level. Rubio was given the nod because he received more second choice support in the Bloomberg poll.

- This obviously also has Cruz finishing third in his home state. That, too, may be something of a leap of faith.

Here's what happens:

| SEC Primary Delegate Allocation Simulation | |||||||||

| Candidate | Bloomberg Poll | Alabama | Arkansas | Georgia | Oklahoma | Tennessee | Texas | Virginia | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trump | 37% | 28 | 22 | 46 | 19 | 33 | 95 | 20 | 263 |

| Rubio | 20% | 15 | 11 | 22 | 12 | 17 | 48 | 11 | 136 |

| Cruz | 20% | 7 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 65 |

| Carson | 8% | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4 | 4 |

| Kasich | 8% | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 3 | 3 |

Observations:

- With 37% across all seven states and all 75 districts, Trump wins more than 55% of the delegates. This is another example of just how much the Republican delegate rules favor winners/frontrunners.

- Remember, we are assuming that Rubio received just one more vote than Cruz. They are both at roughly 20%, but Rubio has one more vote to push him into second place for the purposes of this exercise. That one vote make a huge difference in the delegate count. Everyone wants to win, but if you cannot win in these SEC primary states, then you definitely don't want to be in third (or lower). Why? In every state but Oklahoma and Virginia, third place means getting shut out of the congressional district haul in most cases in the other five states. This simulated allocation really drives that point home. Again, just one vote separated Rubio and Cruz, but Rubio ends up with more than twice as many delegates. This is a big deal for anyone who is consistently in third on the congressional district level. It means falling further behind in the delegate count. Third place is a bad place to be.

- Statewide, only Trump, Rubio and Cruz clear the qualifying thresholds -- 20% in Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee and Texas; 15% in Arkansas and Oklahoma. While that would mean a lot at-large delegates for Trump and that Rubio and Cruz would be allocated a similar share of at-large delegates, Cruz is getting the vast majority of his delegates from the at-large pool. Rubio's advantage is totally within the congressional districts in this exercise.

- Overall, Trump basically carries a nearly 2:1 advantage in vote share over to an almost 2:1 advantage over Rubio in the delegate count. The New York businessman already has a more than 60 delegate advantage in the real delegate count. Not even counting the other four states allocating delegates on Super Tuesday, this hypothetical allocation of SEC primary delegates would tack another roughly 125 delegates onto that lead. Together, that would be more than the 165 delegates available on March 15 in winner-take-all Florida and Ohio. There are a number of comeback scenarios out there that are predicated on those 165 delegates.

- Imagine if Rubio and/or Cruz slip below 20%. That would mean not qualifying delegates in the four most delegate-rich states. That would definitely be true statewide with respect to the at-large delegates, but would also apply to some of the congressional district delegates in some of those states.

Monday, February 22, 2016

A South Carolina Delegate Post

South Carolina was different in 2016 than it has been in the recent past.

The first and most obvious difference is that Donald Trump won all 50 of the delegates in the Palmetto state Republican primary. Four years ago, for example, Newt Gingrich was victorious by a larger margin (statewide), but ran behind Mitt Romney in the first district, losing those delegates. Even George W. Bush won by a similar margin, but lost the first district to John McCain in 2000. The 50 delegate sweep Trump pulled off in the first in the South primary Saturday night, then, is not something that is often witnessed out of South Carolina.

However, that is a pretty minor point in the grand scheme of things. After all, even including a case like 2008, in which Mike Huckabee won two districts, his delegate grab was still much smaller than the share the winner, John McCain, left the state with. It was near winner-take-all as a result.

Yet, that is just it. Near winner-take-all or completely so, the delegate take from South Carolina was different in 2016 than it has been in the last two cycles. In both 2008 and 2012, the South Carolina Republican Party incurred a 50% penalty from the Republican National Committee for trying to stay first in the South (or ahead of Florida in those two years). A less messy calendar (formation) and an underlying rules change helped. Yes, a stronger penalty kept potential rogue states in line for 2016, but even if there had been repeat rogue activity from Florida or North Carolina, another RNC rules change even further insulated the four carve-out states. Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina all had at least a month before the next earliest contest to schedule their contests if other states jumped into February. In the past, the carve-outs moving to anything ahead of February meant they ended up with a penalty like any other rogue state.

Those changes have had implications for 2016 already. New Hampshire yielded Trump delegate surplus 50% greater than the one Mitt Romney emerged with in 2012. Most of that is directly attributable to the fact that Granite state Republicans also had a penalty-reduced delegation four years ago. That is even clearer in light of the fact that Romney received a higher share of the vote in New Hampshire in 2012 than Trump did in 2016.

Further south, the story is similar. Gingrich won by more, but left South Carolina +21 in the delegate count at best. And that was a delegation cut in half. Trump, on the other hand, added all 50 (unpenalized) delegates from South Carolina to his total. That is a more than 100% increase in the delegate cushion the winner got from the Palmetto state primary, cycle over cycle.

If this process is about delegates -- and as March approaches, it is -- then that +50 is a big deal. A 21 delegate surplus is not nothing, but all that did for Gingrich was help the former speaker close the overall delegate gap he faced against Romney. The former Massachusetts governor's total was fueled by the endorsements of then-unbound party delegates before the Florida primary at the end of January 2012.

FHQ raises that non-compliant 2012 winner-take-all primary in Florida for a reason. It was winning those 50 delegates that got Romney off to a delegate lead that the other vying for the nomination could not catch as the primary calendar wended its way through more and more events.

South Carolina is that early calendar delegate boost for Trump in 2016 that Florida was in 2012 for Mitt Romney. There are not a lot of +50s out there, but two are on March 15 and both -- Florida and Ohio -- will say a lot about whether Trump ends up in same position Romney ultimately was in 2012.

The first and most obvious difference is that Donald Trump won all 50 of the delegates in the Palmetto state Republican primary. Four years ago, for example, Newt Gingrich was victorious by a larger margin (statewide), but ran behind Mitt Romney in the first district, losing those delegates. Even George W. Bush won by a similar margin, but lost the first district to John McCain in 2000. The 50 delegate sweep Trump pulled off in the first in the South primary Saturday night, then, is not something that is often witnessed out of South Carolina.

However, that is a pretty minor point in the grand scheme of things. After all, even including a case like 2008, in which Mike Huckabee won two districts, his delegate grab was still much smaller than the share the winner, John McCain, left the state with. It was near winner-take-all as a result.

Yet, that is just it. Near winner-take-all or completely so, the delegate take from South Carolina was different in 2016 than it has been in the last two cycles. In both 2008 and 2012, the South Carolina Republican Party incurred a 50% penalty from the Republican National Committee for trying to stay first in the South (or ahead of Florida in those two years). A less messy calendar (formation) and an underlying rules change helped. Yes, a stronger penalty kept potential rogue states in line for 2016, but even if there had been repeat rogue activity from Florida or North Carolina, another RNC rules change even further insulated the four carve-out states. Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina all had at least a month before the next earliest contest to schedule their contests if other states jumped into February. In the past, the carve-outs moving to anything ahead of February meant they ended up with a penalty like any other rogue state.

Those changes have had implications for 2016 already. New Hampshire yielded Trump delegate surplus 50% greater than the one Mitt Romney emerged with in 2012. Most of that is directly attributable to the fact that Granite state Republicans also had a penalty-reduced delegation four years ago. That is even clearer in light of the fact that Romney received a higher share of the vote in New Hampshire in 2012 than Trump did in 2016.

Further south, the story is similar. Gingrich won by more, but left South Carolina +21 in the delegate count at best. And that was a delegation cut in half. Trump, on the other hand, added all 50 (unpenalized) delegates from South Carolina to his total. That is a more than 100% increase in the delegate cushion the winner got from the Palmetto state primary, cycle over cycle.

If this process is about delegates -- and as March approaches, it is -- then that +50 is a big deal. A 21 delegate surplus is not nothing, but all that did for Gingrich was help the former speaker close the overall delegate gap he faced against Romney. The former Massachusetts governor's total was fueled by the endorsements of then-unbound party delegates before the Florida primary at the end of January 2012.

FHQ raises that non-compliant 2012 winner-take-all primary in Florida for a reason. It was winning those 50 delegates that got Romney off to a delegate lead that the other vying for the nomination could not catch as the primary calendar wended its way through more and more events.

South Carolina is that early calendar delegate boost for Trump in 2016 that Florida was in 2012 for Mitt Romney. There are not a lot of +50s out there, but two are on March 15 and both -- Florida and Ohio -- will say a lot about whether Trump ends up in same position Romney ultimately was in 2012.

Thursday, February 11, 2016

Bill Eliminating Presidential Primary After 2016 Clears Arizona House

The Arizona House on Wednesday, February 10, passed HB 2567 by a vote of 37-22. The legislation would appropriate state funds to fully fund the 2016 presidential preference election in the Grand Canyon state but also eliminate the election in future cycles.

The impetus behind the move appears to be budgetary, but there may also be some secondary implications. Arizona Secretary of State Michele Reagan made clear in a state House Appropriations Committee hearing that, first, the statewide election carries a cost of nearly $10 million and, second, is a tab that should be picked up by the state parties in Arizona. The secretary called the possibilities for state parties absent state funding "limitless". However, that ignores the fact that state parties in a state as large as Arizona do not typically caucus or spend upwards of $10 million for a party-run primary. Rather than limitless, then, the likely outcome is a shift to a caucus/convention system to select delegates in the presidential nomination process.

A similar bill was proposed in 2012, but went nowhere. That effort, like the current one, had the support of county elections administrators in the states, who have long supported ceding state control of the nominating contest to the parties.

--

While this bill is still early in the legislative process, it could lead to a potentially noteworthy change for the 2020 cycle. If the bill passes, is signed into law and repeals the presidential preference election, that effectively makes Arizona a caucus state.

It was not that long ago that Arizona Democrats pushed for caucuses as a means of joining the carve-out states at the beginning of the primary calendar. The Arizona pitch to the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee in 2006 included plans to shift to caucuses. At the time the national party, in an attempt to diversify the primary electorate on the early calendar, wanted to add a southern state and a western state as well as a primary state and a caucus state (that at the time could be put in a slot in front of New Hampshire on the calendar). South Carolina gained the southern primary spot and Nevada was slotted into the western caucus spot.

Nevada has had its share of issues on both sides of the political aisle in the last two presidential nomination cycles. That, in turn, has led to some discussion about whether the Silver state is on the chopping block as an early state. If the national parties -- both of them, not just the DNC -- want a western caucus state up front and want to replace Nevada, an Arizona caucus might provide an alternative.

File that one away for 2017-2018, though.

--

Thanks to Richard Winger at Ballot Access News for passing news of the Arizona bill along.

The impetus behind the move appears to be budgetary, but there may also be some secondary implications. Arizona Secretary of State Michele Reagan made clear in a state House Appropriations Committee hearing that, first, the statewide election carries a cost of nearly $10 million and, second, is a tab that should be picked up by the state parties in Arizona. The secretary called the possibilities for state parties absent state funding "limitless". However, that ignores the fact that state parties in a state as large as Arizona do not typically caucus or spend upwards of $10 million for a party-run primary. Rather than limitless, then, the likely outcome is a shift to a caucus/convention system to select delegates in the presidential nomination process.

A similar bill was proposed in 2012, but went nowhere. That effort, like the current one, had the support of county elections administrators in the states, who have long supported ceding state control of the nominating contest to the parties.

--

While this bill is still early in the legislative process, it could lead to a potentially noteworthy change for the 2020 cycle. If the bill passes, is signed into law and repeals the presidential preference election, that effectively makes Arizona a caucus state.

It was not that long ago that Arizona Democrats pushed for caucuses as a means of joining the carve-out states at the beginning of the primary calendar. The Arizona pitch to the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee in 2006 included plans to shift to caucuses. At the time the national party, in an attempt to diversify the primary electorate on the early calendar, wanted to add a southern state and a western state as well as a primary state and a caucus state (that at the time could be put in a slot in front of New Hampshire on the calendar). South Carolina gained the southern primary spot and Nevada was slotted into the western caucus spot.

Nevada has had its share of issues on both sides of the political aisle in the last two presidential nomination cycles. That, in turn, has led to some discussion about whether the Silver state is on the chopping block as an early state. If the national parties -- both of them, not just the DNC -- want a western caucus state up front and want to replace Nevada, an Arizona caucus might provide an alternative.

File that one away for 2017-2018, though.

--

Thanks to Richard Winger at Ballot Access News for passing news of the Arizona bill along.

Wednesday, February 10, 2016

The New Hampshire Delegate Count and Beyond -- Automatic Delegates

There was some confusion throughout New Hampshire primary day about just how many of the Republican delegates were on the line in the Granite state. If one looks at New Hampshire state law, it sets the basic terms of delegate allocation in the state. The shorthand of this is that the secretary of state allocates delegates to the national convention to candidates who receive more than 10 percent of the statewide vote in the New Hampshire primary.

That is just "delegates", not at-large delegates or district delegates. Just delegates.

However, the New Hampshire Republican Party has traditionally pooled its at-large and district delegates and allocated them proportionally based on the statewide result. According to party bylaws (see Article II, Section 1 and Article III), though, the three party or automatic delegates have traditionally been unbound. The state party chair, the national committeeman and national committeewoman are prohibited from supporting any candidates. The party rules keep them "neutral".

That would seem to indicate that only 20 of the 23 New Hampshire delegates were at stake in Tuesday's primary. That was how FHQ interpreted the rules and we were not alone. That has been the way that delegates have been allocated in New Hampshire in the Republican contest.1

But this interpretation ignores changes made to the national party delegate selection rules for 2016. New to the Rules of the Republican Party for this cycle is a requirement binding delegates to candidates based on the results of statewide contests like the New Hampshire primary and the Iowa caucuses a week ago.

That rule, Rule 16(a)(1), states:

That fairly inclusive-seeming definition leaves open to interpretation just how state parties like New Hampshire's or Virginia's deal with the potential ambiguity in the national party rules as compared to state party bylaws that explicitly keep the party/automatic delegates neutral or unbound. Typically, the RNC has left much of the minutiae of delegate selection up to the states to decide.

Yet, in December, FHQ was told that there were no unbound delegates at the outset of the Republican nomination process. There can be unbound delegates, but only if they are released by candidates who have withdrawn from the race. That meant that in the 40 percent of states where state party rules left the automatic delegates unbound there was something of a conflict. That is what prompted us to begin adding riders like the following to the FHQ explainers on delegate allocation at the state level. Here's an example from the Virginia post:

In New Hampshire, then, the party delegates are lumped in with the full allotment of delegates and allocated proportionally. The same would be true in Virginia (rendering Morton Blackwell's endorsement of Ted Cruz somewhat moot). A state like Tennessee, where only the at-large delegates are proportionally allocated based on the statewide results (and the district level delegates based on the congressional district results), those party delegates would treated as another three at-large delegates.

This is bigger than New Hampshire, then. Other state are affected as well, and FHQ's state-level allocation primers will be updated to reflect the clarified interpretation of the rules.

--

1 Of course, it has been since 2000 that that traditional method had been used. Penalties imposed by the national party for going too early in the last two competitive cycles -- 2008 and 2012 -- meant that New Hampshire lost its automatic delegates. New Hampshire is rules compliant for 2016 and they have their automatic delegates.

That is just "delegates", not at-large delegates or district delegates. Just delegates.

However, the New Hampshire Republican Party has traditionally pooled its at-large and district delegates and allocated them proportionally based on the statewide result. According to party bylaws (see Article II, Section 1 and Article III), though, the three party or automatic delegates have traditionally been unbound. The state party chair, the national committeeman and national committeewoman are prohibited from supporting any candidates. The party rules keep them "neutral".

That would seem to indicate that only 20 of the 23 New Hampshire delegates were at stake in Tuesday's primary. That was how FHQ interpreted the rules and we were not alone. That has been the way that delegates have been allocated in New Hampshire in the Republican contest.1

But this interpretation ignores changes made to the national party delegate selection rules for 2016. New to the Rules of the Republican Party for this cycle is a requirement binding delegates to candidates based on the results of statewide contests like the New Hampshire primary and the Iowa caucuses a week ago.

That rule, Rule 16(a)(1), states:

Any statewide presidential preference vote that permits a choice among candidates for the Republican nomination for President of the United States in a primary, caucuses, or a state convention must be used to allocate and bind the state’s delegation to the national convention in either a proportional or winner-take-all manner, except for delegates and alternate delegates who appear on a ballot in a statewide election and are elected directly by primary voters. [Emphasis FHQ's]Like the New Hampshire state law, the terms of the Republican Party rule are ambiguous. It just says that a state's delegates must be allocated proportionally or winner-take-all based on primary or caucus results. There is no distinction between types of delegates. It is just delegates or in this case a state's delegation.

That fairly inclusive-seeming definition leaves open to interpretation just how state parties like New Hampshire's or Virginia's deal with the potential ambiguity in the national party rules as compared to state party bylaws that explicitly keep the party/automatic delegates neutral or unbound. Typically, the RNC has left much of the minutiae of delegate selection up to the states to decide.

Yet, in December, FHQ was told that there were no unbound delegates at the outset of the Republican nomination process. There can be unbound delegates, but only if they are released by candidates who have withdrawn from the race. That meant that in the 40 percent of states where state party rules left the automatic delegates unbound there was something of a conflict. That is what prompted us to begin adding riders like the following to the FHQ explainers on delegate allocation at the state level. Here's an example from the Virginia post:

The automatic delegates -- the state party chair, national committeeman and national committeewoman -- from Virginia are explicitly unbound according to the September resolutions adopted by the state party. That has been the case in the past, but FHQ was informed in recent conversations with the Republican National Committee that Rule 16(a)(1) binds all delegates from a delegation. The only exception is for delegates elected directly (on the ballot). That does not include party/automatic delegates. How those delegates are allocated/bound when the state rules are not clear on their allocation is a bit of an unknown and something of a wildcard.The Republican National Committee has a more rigid interpretation of Rule 16(a)(1) and its effect on the binding of the three party delegates when such a binding process is not specified on the state level. In a January 29 memo to RNC members, the RNC general counsel's office, citing both Rule 16(a)(1) and the November call to the 2016 convention, detailed the binding of party delegates in those states. In a state where the allocation of party delegates is not specified, those delegates are to be treated as at-large delegates and allocated in a manner consistent with the allocation of that subset of delegates.

In New Hampshire, then, the party delegates are lumped in with the full allotment of delegates and allocated proportionally. The same would be true in Virginia (rendering Morton Blackwell's endorsement of Ted Cruz somewhat moot). A state like Tennessee, where only the at-large delegates are proportionally allocated based on the statewide results (and the district level delegates based on the congressional district results), those party delegates would treated as another three at-large delegates.

This is bigger than New Hampshire, then. Other state are affected as well, and FHQ's state-level allocation primers will be updated to reflect the clarified interpretation of the rules.

--

1 Of course, it has been since 2000 that that traditional method had been used. Penalties imposed by the national party for going too early in the last two competitive cycles -- 2008 and 2012 -- meant that New Hampshire lost its automatic delegates. New Hampshire is rules compliant for 2016 and they have their automatic delegates.

Monday, February 8, 2016

Two Things to Watch in the New Hampshire Delegate Race on the Republican Side

UPDATED 2/9/16

Mainly the candidates for the Republican presidential nomination will be fighting for a win and/or jockeying for position in Tuesday's primary. But there are couple of factors to watch as the returns come in that will affect the resulting delegate count coming out of the Granite state.

While New Hampshire does not offer a windfall of delegates, depending on how the voting shakes out the winner could end up with a surplus of delegates -- under the New Hampshire law that guides the allocation process -- that far outstrips the one delegate that separated first from third place in Iowa's caucuses. That surplus hinges on two things:

First, how many candidates finish over the 10 percent threshold necessary to claim any delegates? The current polling in the Granite state on the Republican race has Donald Trump well out in front. And while those numbers may not translate to votes, that fact does underline something perhaps more important for the candidates immediately behind the real estate mogul: the fluidity of polling in New Hampshire. Accurate or not, the polling has a number of candidates hovering around that 10 percent mark; something that has not gotten enough attention amid discussions of debate performances and impending voting.

Unlike in some other states, candidates in the New Hampshire primary receive a share of delegates in proportion to their vote. If a candidate wins 11 percent of the vote, that candidate is allocated 11 percent of the delegates. Other states proportionally allocate delegates in a manner that considers a candidate's share of the vote among just the qualifying candidates; those who meet or exceed the threshold. In that scenario, a candidate who wins 11 percent of the vote would be awarded slightly more than 11 percent of the delegates.

This is an important distinction because it leaves some number of unallocated delegates because of the threshold.

The second factor to keep an eye on as the votes are being counted tomorrow night is how much of a percentage of the total vote are the candidates not qualifying for delegates taking. A larger under the threshold percentage means a greater number of unallocated delegates. If, for instance, Donald Trump wins 31 percent of the vote and Marco Rubio places second with 15 percent, but Bush, Cruz and Kasich dip below 10 percent, that leaves 54% of the vote below the threshold. That leaves over half of the delegates unallocated.

Only, that unallocated portion is awarded to the winner of the primary. Trump would claim seven delegates for the 31 percent won to the three Rubio would win for pulling in 15 percent of the vote. However, an additional 12 delegates -- that 54 percent share -- would be allocated to Trump.

Trump, then, would leave the Granite state with 16 delegate surplus. Again, that would be 16 times greater than the cushion Cruz brought out of Iowa. This is an important point. No, not necessarily for Trump specifically, but it is these sorts rules-based differences that can be meaningful in a protracted race for a presidential nomination. If it becomes a state-to-state battle, then these delegate margins start to matter more and more.

To drive home the point about the New Hampshire rules -- and these two factors in particular -- let's go back and assume that Trump and Rubio keep their respective shares, Cruz and Kasich hold steady at around 13 percent (rather than falling below the threshold) and Jeb Bush manages to stay over the 10 percent threshold (to say, 11 percent). That is five candidates over the threshold set by New Hampshire state law with a collective 83 percent of the vote. That leaves only 17 percent unaccounted for under the threshold. Just five delegates.

After Trump takes his seven delegates and Rubio his three, Cruz and Kasich each also grab three and Bush two more. The five "unallocated" delegates are added to Trump's count for 12 delegates total and just a nine delegate surplus when compared to the 16 delegate cushion in the simulation with just two candidates above the threshold and the others below it gobbling up a significant percentage of the total vote. As the number of candidates above the threshold increases, the percentage below the threshold tends to decrease.

No, there are not a lot of delegates on the line in New Hampshire on February 9. However, the rules are in place to make New Hampshire potentially more valuable than Iowa proved to be and perhaps even some larger proportional states deeper into the calendar.

Mainly the candidates for the Republican presidential nomination will be fighting for a win and/or jockeying for position in Tuesday's primary. But there are couple of factors to watch as the returns come in that will affect the resulting delegate count coming out of the Granite state.

While New Hampshire does not offer a windfall of delegates, depending on how the voting shakes out the winner could end up with a surplus of delegates -- under the New Hampshire law that guides the allocation process -- that far outstrips the one delegate that separated first from third place in Iowa's caucuses. That surplus hinges on two things:

First, how many candidates finish over the 10 percent threshold necessary to claim any delegates? The current polling in the Granite state on the Republican race has Donald Trump well out in front. And while those numbers may not translate to votes, that fact does underline something perhaps more important for the candidates immediately behind the real estate mogul: the fluidity of polling in New Hampshire. Accurate or not, the polling has a number of candidates hovering around that 10 percent mark; something that has not gotten enough attention amid discussions of debate performances and impending voting.

Unlike in some other states, candidates in the New Hampshire primary receive a share of delegates in proportion to their vote. If a candidate wins 11 percent of the vote, that candidate is allocated 11 percent of the delegates. Other states proportionally allocate delegates in a manner that considers a candidate's share of the vote among just the qualifying candidates; those who meet or exceed the threshold. In that scenario, a candidate who wins 11 percent of the vote would be awarded slightly more than 11 percent of the delegates.

This is an important distinction because it leaves some number of unallocated delegates because of the threshold.

The second factor to keep an eye on as the votes are being counted tomorrow night is how much of a percentage of the total vote are the candidates not qualifying for delegates taking. A larger under the threshold percentage means a greater number of unallocated delegates. If, for instance, Donald Trump wins 31 percent of the vote and Marco Rubio places second with 15 percent, but Bush, Cruz and Kasich dip below 10 percent, that leaves 54% of the vote below the threshold. That leaves over half of the delegates unallocated.

Only, that unallocated portion is awarded to the winner of the primary. Trump would claim seven delegates for the 31 percent won to the three Rubio would win for pulling in 15 percent of the vote. However, an additional 12 delegates -- that 54 percent share -- would be allocated to Trump.

Trump, then, would leave the Granite state with 16 delegate surplus. Again, that would be 16 times greater than the cushion Cruz brought out of Iowa. This is an important point. No, not necessarily for Trump specifically, but it is these sorts rules-based differences that can be meaningful in a protracted race for a presidential nomination. If it becomes a state-to-state battle, then these delegate margins start to matter more and more.

To drive home the point about the New Hampshire rules -- and these two factors in particular -- let's go back and assume that Trump and Rubio keep their respective shares, Cruz and Kasich hold steady at around 13 percent (rather than falling below the threshold) and Jeb Bush manages to stay over the 10 percent threshold (to say, 11 percent). That is five candidates over the threshold set by New Hampshire state law with a collective 83 percent of the vote. That leaves only 17 percent unaccounted for under the threshold. Just five delegates.

After Trump takes his seven delegates and Rubio his three, Cruz and Kasich each also grab three and Bush two more. The five "unallocated" delegates are added to Trump's count for 12 delegates total and just a nine delegate surplus when compared to the 16 delegate cushion in the simulation with just two candidates above the threshold and the others below it gobbling up a significant percentage of the total vote. As the number of candidates above the threshold increases, the percentage below the threshold tends to decrease.

No, there are not a lot of delegates on the line in New Hampshire on February 9. However, the rules are in place to make New Hampshire potentially more valuable than Iowa proved to be and perhaps even some larger proportional states deeper into the calendar.

Saturday, February 6, 2016

2016 Delegate Allocation Over Time

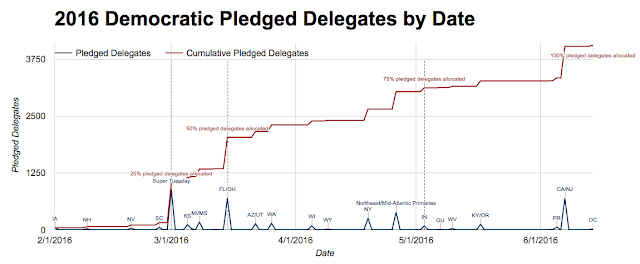

With the first votes in the 2016 presidential nomination contests in, the races have moved out of the invisible primary and into a different phase. Concurrent with that change comes a switch in the basis for discussion. The same polls, fund-raising and endorsement data is still there, but added to that now is chatter about wins and losses and of the chase for the delegates necessary to clinch one of the parties' nominations.

FHQ is guiltier than most of digging down into that chase or the rules governing the allocation of those delegates. However, taking a step back to gain a broader view of the undulations in the process can be just as important.

Compared to the frontloaded calendars of four and eight years ago, the 2016 calendar is completely different. The February start to the 2016 process is a month later than both of the previous cycles and most of the action is packed into just two months, March and April. Eight years ago, both parties had allocated more than 80% their delegates after the contests on the first Tuesday of March. At that same point on the calendar in 2012, roughly one-third of the total number of delegates had been allocated.

In 2016?

For the current cycle, the first Tuesday in March will be the one-quarter point on the cumulative delegates allocated tally in both parties.

The national parties informally coordinated the later start and unlike 2012, actually got their way. But the allocation of delegates is also pushed into a smaller space on the 2016 calendar than was the case in 2012. The de facto national primary on February 5, 2008 when 23 Democratic and 21 Republican state voted was perhaps even more compressed than is the case in 2016.

But the development of the 2016 calendar is about the back end of the calendar as well. Four southern states -- Arkansas, Kentucky, North Carolina and Texas -- all moved from May dates in 2012 to dates in the first half of March 2016. It is the shifting of the delegates in those states along with the later start that has led to the compressed -- March and April -- calendar of events in 2016.

Whereas the middle 50 percent of the allocation -- between the 25 percent and 75 percent points on the calendar -- were bookended by early March and late May spots in 2012, in 2016 that middle 50 percent window in from early March to late April with a very quick ramping up of allocation between March 1 and March 15 on both parties' calendars. After March 15, the climb from the 50 percent point to the 75 percent point is much more gradual and even more subtle after that until a late flourish of allocation in early June to close the process out.

This has strategic implications. The remaining candidates -- those not winnowed by the February carve-out state contests -- have a quick burst of primaries and caucuses in the first two weeks of March. All of the active campaigns will want to develop any kind of a lead in the delegate count by then. Though the rules open up a bit on the Republican side with the closing of the proportionality window, there are limited winner-take-all states to take advantage of after that. That means that any delegate lead in either party will be difficult to close for those challenging to overtake the leader in the count at that 50 percent point.

That is because the states after the middle of March are mostly going to distribute their delegates to multiple candidates in various ways. Both catching up to a delegate leader and closing out a nomination become steeper climbs in such an environment.

Below is a look at the how cumulative growth in delegates allocated progresses in both parties in 2016.

Of note is that the Democrats are about a week behind the Republican allocation after March 1. That has much to do with there being a bevy of southern conservative states early in the process. Both parties have some form of bonus delegate calculation that that rewards party loyalty (as measured by past voting history). There are more Republican bonuses up front than on the Democratic side. Those states carry more weight in the Republican process than for the Democrats.

Note also that there are two figures for the Democrats. The first accounts for the cumulative allocation of all of the Democratic delegates. However, that includes superdelegates that will not be pledged to candidates based on the results of primaries and caucuses. When the 712 superdelegates are backed out -- see the final figure -- the picture looks largely the same among the 4051 pledged delegates. The pattern is virtually the same.

--

The Republicans

You can also find this image included with the delegate allocation information for the Republican process.

--

The Democrats

FHQ is guiltier than most of digging down into that chase or the rules governing the allocation of those delegates. However, taking a step back to gain a broader view of the undulations in the process can be just as important.

Compared to the frontloaded calendars of four and eight years ago, the 2016 calendar is completely different. The February start to the 2016 process is a month later than both of the previous cycles and most of the action is packed into just two months, March and April. Eight years ago, both parties had allocated more than 80% their delegates after the contests on the first Tuesday of March. At that same point on the calendar in 2012, roughly one-third of the total number of delegates had been allocated.

In 2016?

For the current cycle, the first Tuesday in March will be the one-quarter point on the cumulative delegates allocated tally in both parties.

The national parties informally coordinated the later start and unlike 2012, actually got their way. But the allocation of delegates is also pushed into a smaller space on the 2016 calendar than was the case in 2012. The de facto national primary on February 5, 2008 when 23 Democratic and 21 Republican state voted was perhaps even more compressed than is the case in 2016.

But the development of the 2016 calendar is about the back end of the calendar as well. Four southern states -- Arkansas, Kentucky, North Carolina and Texas -- all moved from May dates in 2012 to dates in the first half of March 2016. It is the shifting of the delegates in those states along with the later start that has led to the compressed -- March and April -- calendar of events in 2016.

Whereas the middle 50 percent of the allocation -- between the 25 percent and 75 percent points on the calendar -- were bookended by early March and late May spots in 2012, in 2016 that middle 50 percent window in from early March to late April with a very quick ramping up of allocation between March 1 and March 15 on both parties' calendars. After March 15, the climb from the 50 percent point to the 75 percent point is much more gradual and even more subtle after that until a late flourish of allocation in early June to close the process out.

This has strategic implications. The remaining candidates -- those not winnowed by the February carve-out state contests -- have a quick burst of primaries and caucuses in the first two weeks of March. All of the active campaigns will want to develop any kind of a lead in the delegate count by then. Though the rules open up a bit on the Republican side with the closing of the proportionality window, there are limited winner-take-all states to take advantage of after that. That means that any delegate lead in either party will be difficult to close for those challenging to overtake the leader in the count at that 50 percent point.

That is because the states after the middle of March are mostly going to distribute their delegates to multiple candidates in various ways. Both catching up to a delegate leader and closing out a nomination become steeper climbs in such an environment.

Below is a look at the how cumulative growth in delegates allocated progresses in both parties in 2016.

Of note is that the Democrats are about a week behind the Republican allocation after March 1. That has much to do with there being a bevy of southern conservative states early in the process. Both parties have some form of bonus delegate calculation that that rewards party loyalty (as measured by past voting history). There are more Republican bonuses up front than on the Democratic side. Those states carry more weight in the Republican process than for the Democrats.