Part of the calendar package that the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee (DNCRBC) adopted early last month was a deadline for states that were at that time granted conditional waivers to be able to schedule primaries and caucuses in the pre-window period. That deadline -- January 5, 2023 -- was put in place as an early marker by which those states were to have shown state-specific progress toward the goal of moving their contests into the prescribed positions.

Three of the five states -- South Carolina, Nevada and Michigan -- are in good shape after January 5 based on a variety of factors. South Carolina's state parties, and not the state government, select the date of the presidential primary, Nevada is on the prescribed date already, and the 2022 midterms left Democrats in unified control of state government in Michigan. That puts each on a glide path to compliance with the likely DNC rules for the 2024 presidential nomination cycle.

But the remaining two states have run into problems and failed to meet the January 5 deadline. The easy explanation is that both New Hampshire and Georgia have a Republicans problem. Republicans control state government in New Hampshire and the secretary of state's office in Georgia.

However, both states were required to do different things by the DNCRBC before January 5 in order to retain their waivers.

Georgia Democrats had to win over Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) and convince him to move the presidential primary to February 13. They have failed to do so to this point. Yet, the secretary's office has provided the criteria by which the primary could occur earlier: 1) the Democratic and Republican presidential primaries must occur concurrently (as has been the custom in the Peach state and most states with state-run primaries, for that matter) and 2) the primary cannot be so early that it leads to delegate penalties from one or both national parties. February 13 does not work under those criteria, but a date later in the pre-window period may.

New Hampshire Democrats, on the other hand, had a much higher bar to clear before January 5. Although the secretary of state selects the date on which the presidential primary in the Granite state falls -- just as in Georgia -- the DNCRBC instead targeted the legislative process. The panel expected progress toward changing state law to specify the February 6, 2024 date on which the DNC has proposed to schedule the New Hampshire primary and to expand voting to include no-excuse absentee balloting in the state. Democrats in New Hampshire would have likely balked at those demands anyway, but had no real recourse with Republicans uninterested in making those changes in unified control of state government.

But FHQ will not rehash all of that again. One can always go read about the New Hampshire defense of the first-in-the-nation law, the lose-lose situation in which the Democratic Party there finds itself for the 2024 cycle and what happened in 1984 when New Hampshire was in a similar predicament (and what that might mean for 2024).

Instead, let's examine where this process has been and where it is likely to go given that it looks like both the DNCRBC and New Hampshire Democrats may be digging in for an extended standoff.

Where this has been

I. In the lead up to the December 2 DNCRBC meeting it looked as if the panel might take the path of least resistance toward change: knock Iowa from its perch atop the calendar, move every other early state up and add an Iowa replacement to the mix. That set expectations high that New Hampshire Democrats would be able to easily protect their traditional first primary position. When the Biden calendar proposal was revealed and adopted by the DNCRBC, those high expectations were dashed and New Hampshire Democrats reacted swiftly and defiantly.

II. But it was not just that South Carolina supplanted New Hampshire in the president's plan that rankled Democrats in the Granite state. Sure, that stuck in their craws, but the aforementioned hoops through which the DNCRBC required the New Hampshire Democratic Party to jump added insult to injury. The herculean tasks made it appear as if the DNCRBC had only provided the New Hampshire primary a waiver-in-name-only; a hollow protection of the state's first-in-the-nation status in the Democratic process given impossibly high requirements. Again, the reaction was (pre-Christmas) defiance.

III. Then came January 5. And the reaction was again defiance but this time mixed with a request that the DNCRBC not punish New Hampshire Democrats for being unable to meet "unrealistic and unattainable" goals. That was further buttressed by the New Hampshire Republicans in power from the governor to the legislative leaders and the secretary of state on down signaling that no changes were imminent.

Where it is going

IV. However, since there are clear roadblocks to compliance in the cases of both New Hampshire and Georgia, an extension was granted. That grace period will provide both sides -- the DNCRBC and, in this case, New Hampshire Democrats -- some time to consider alternatives.

V. Extension or not, all states conditionally granted waivers to hold nominating contests in the pre-window have until February 1 -- the night before the February 2-4 Democratic Winter meeting kicks off -- to complete all action on making the changes required by the DNRBC. That early February meeting is when the DNC is set to vote on the calendar proposal adopted by the DNCRBC in December.

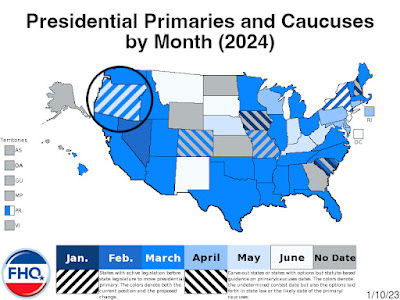

VI. Following the final DNC adoption of the calendar rules for 2024 state parties will spend the spring finalizing draft delegate selection plans, including when the state's nominating contest is scheduled to occur. Those plans must face a public comment period of at least one month before being submitted for DNCRBC review before the early stages of May 2023.

VII. Thereafter, any points of contention -- any noncompliance issues in state delegate selection plans -- will be hammered out between the state parties in question and the DNCRBC before final approval is granted (or not) during the summer and into the fall. Noncompliance at that stage will trigger penalties. The automatic penalty for a timing violation is a 50 percent reduction in a state's delegation. But if the New Hampshire secretary of state schedules the presidential primary for any date other than the one prescribed by DNC rules and Granite state Democrats go along with it (defying DNC rules), then the party is likely to draw the Florida/Michigan treatment from the DNCRBC. It is also at the discretion of the DNCRBC to go beyond the 50 percent penalty and in the case of Florida and Michigan, both of which planned to and held noncompliant primaries in 2008, that penalty was a raised to 100 percent. [Of course, there are caveats to that penalty.]

FHQ will stop there. To go further is to speculate more than I am willing given the intended scope here.

The point is less to lay out the above timeline than it is to show that New Hampshire Democrats have already had around three opportunities to respond to the DNCRBC concerning the proposed changes to the calendar. They will have roughly four more chances to do so in the coming year both before the national party rules are finalized and after.

How they respond (or continue to respond) matters.

There is a reason FHQ said this when the president's calendar plan was released on the eve of the December DNCRBC meeting:

"If I'm folks in NH, I'm real quiet right now other than to say, "There is a state law. We will defer to the secretary of state on the matter as the law requires." That's it. Quietly and happily go along for the ride and say you did everything you could to lobby for a change."

That drew the ire of some in New Hampshire at the time, but it reflects the DNC rules and the nature of how they have been interpreted over time. Those rules, specifically Rule 21, require state parties to have "acted in good faith" and to have taken "all provable positive steps" towards making any changes on the state level to bring the state's delegate selection plan into compliance with DNC rules.

DNCRBC co-Chair Jim Roosevelt echoed the language in that rule when he recently discussed the New Hampshire and Georgia situations with NPR.

"Hopefully there will be flexibility," said Jim Roosevelt, co-chair of the Rules and Bylaws Committee, of his colleagues. The committee is likely to meet and vote on granting the extensions in the coming weeks before a planned DNC-wide vote to approve or deny the new calendar at a meeting in Philadelphia in early February.

Roosevelt said the DNC has worked with other states in the past as long as they can show they are making their "best effort" and taking "provable, positive steps."

Notice that. Roosevelt mentions both DNCRBC-side flexibility on providing more time but also in working with state parties that will meet them in the middle somewhere.

New Hampshire Democrats have certainly leaned in on the law the state has on the books to protect its first-in-the-nation status in the time since the calendar proposal was unveiled. But whether they have to this point made their "best efforts" at change or taken "provable, positive steps" toward compliance is debatable (if not in the eye of the beholder).

The DNC will likely adopt some calendar plan next month in Philadelphia. There may even be some changes to accommodate New Hampshire and/or Georgia. But if the New Hampshire primary remains tethered to the Nevada primary on February 6 in those adopted rules, then how New Hampshire Democrats react may go some way toward telling interested onlookers how the DNCRBC is likely to respond.

Does the New Hampshire Democratic Party delegate selection plan submitted to the DNCRBC for review go along with the proposed February 6 date or leave that part open pending the decision of Secretary of State Scanlan (R)?

Do Democrats in the New Hampshire state legislature make any moves to change the primary date (futile though those efforts may ultimately be)? Do they make some attempt to consolidate the Democratic primary with town meetings in March (as the primary was initially intended to be prior to 1975)?

Does the New Hampshire Democratic Party offer to hold a party-run contest?

Those are all signals of, if not outright, good faith moves and/or provable, positive steps. And those steps may in some cases still trigger a 50 percent delegate reduction, but it may also help the party avoid making the New Hampshire primary into a "state-sponsored public opinion poll" in the 2024 Democratic presidential nomination process.

Continued defiance in the eyes of the DNCRBC will not help avoid that fate.

But ultimately New Hampshire Democrats may bank on the fact that the DNC will eventually cave and not be able to enforce any effort to keep a swing state delegation out of the convention. Of course, a president who wanted to diversify the early calendar who becomes presumptive nominee with little or only token opposition and leads said convention may have some input on the matter.

However, that is a ways down the road and both sides -- New Hampshire Democrats and the DNCRBC -- have some built-in off ramps (as laid out above) along the way. Will either or both take them or will the showdown continue into 2024?

--

Recent posts: